The EU’s European Chemicals Agency prohibits the use of the three neonicotinoids: imidacloprid, clothianidin, and thiamethoxam – already under a partial ban as long ago as 2013. (For more details of the bans on neonicotinoids, click here.)

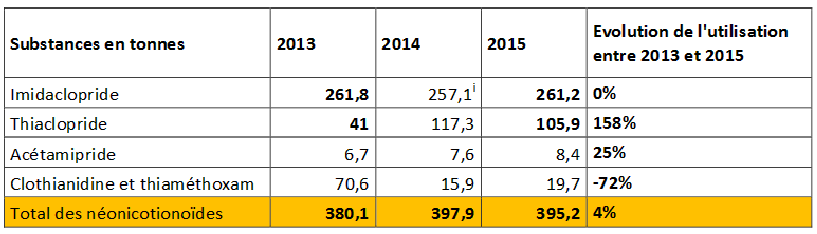

Yet sales of imidacloprid remained constant between 2013 and 2015 despite the ban. This can be explained partially by the exemption given for its use on straw cereals. However,  according to the previous French Ministry of Environment, Imidacloprid has a ‘worrying tendency ‘ to contaminate surface water, and can be absorbed by untreated crops where it lingers for up to 2 years. It is also found in pollen and nectar at toxic levels for bees.

according to the previous French Ministry of Environment, Imidacloprid has a ‘worrying tendency ‘ to contaminate surface water, and can be absorbed by untreated crops where it lingers for up to 2 years. It is also found in pollen and nectar at toxic levels for bees.

Whereas the use of clothianidin and thiamethoxam dropped 72% in three years, it should be noted that these two substances have been replaced by another chemical substance called thiacloprid. Thiacloprid is considered an endocrine disruptor by the EU, yet its use has more than doubled (x2.5) during the period 2013 and 2015. Thiacloprid is used extensively for corn growing.

The new French Government reaffirmed last month its intention to ban the use of seven neonicotinoids as of 1 September 2018 in accordance with France’s new Biodiversity Law set up last year. These seven are:

- Acetamipride,

Sales of neonicotinoids went up 4% in France 2013-2015 despite a European ban. Source: Union Nationale de l’Apiculture Française/UNAF. - Clothianidin,

- Dinotefurance,

- Imidacloprid,

- Nitenpyrame,

- Thiaclopride

- Thiamethoxam.

This reassurance came after a recent embarrassing hiccup within the government where the new Agriculture Minister (new, due to a quick Cabinet re-shuffle) announced he wanted to lift the ban: he was very quickly pulled into line by the Prime Minister.

Last month Science published an article showing an 80% drop in flying insects between 1989 and 2013, blaming the use of neonicotinoids. Last week the journal published a new large-scale field study carried out over two years on the effect of neonicotinoids on honey bees and wild bees. The study confirmed that these pesticides do indeed harm bees. Requested in 2014 by Bayer and Syngenta, the study was carried out by the UK Centre for Ecology and Hydrology and is Europe’s largest field trial, covering 33 sites in the UK, Hungary and Germany. Field studies are considered more reliable than laboratory studies which do not show field-realistic levels of chemicals or environmental conditions; and bees behave differently in the laboratory.

The findings of this latest study were mixed, however. In Hungary, colonies near oilseed rape treated with clothianidin showed a 24% drop in worker bees the following spring (thiamethoxam had no effect); results in the UK were similar. But in Germany there were no lasting effects in honey bee colonies near the treated crops. The explanation for this difference could lie in the fact that the bees in Germany had more access to wild flowers near the fields, rendering them more resilient.

A separate study of honey bees in Canadian maize fields showed up to 4 months of chronic exposure to the pesticides that appear to have persisted from prior plantings, a much longer period of exposure than had been thought. .

Fingers are pointed at both industrial lobbies and farmers, but the results of the field study do show that, used responsibly alongside alternative farming methods in an optimized environment (access to wild flowers and forests for shelter in winter), bees can survive. But it is a delicate balancing act, requiring trust, know-how and constant monitoring.

Is this balancing act sustainable, given the devastating effect erroneous use can have on our bees? Bees save us by pollinating our crops, so we should do all we can to save them.

See also:

To Bee or not to Bee

Bee-killing neonicotinoids to be banned by European Commission

France votes in ban on neonicotinoid insecticides