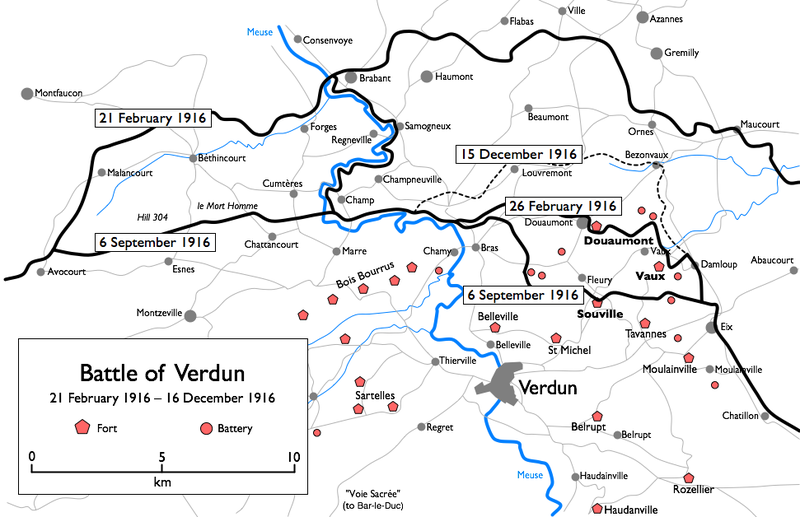

There was once a man who loved his mule; he stabled it in a natural cave next to the ammunition store he and his regiment had built in the forest behind the fortress, near Verdun. It was World War I and he had five mules in his care. ‘Mule’ was his favourite. While all the other mules’ hooves were always smothered in mud, Mule’s hooves never seemed to get dirty, yet he worked just as hard as the others, pulling the laden carts over the uneven earth, carrying the regiment’s artillery to where the next battle was to take place, or to where they decided it was safe to stock it. When the rain slashed down and flooded the trenches, the other mules skidded and often fell and their fur got caked with mud. The mud stuck to them, it dried on them when the sun came out so that by the end of the day it seemed they were wearing grey shrouds. Mule never had such a shroud because he hardly ever fell, and when he did he’d shake his body and the mud rolled off him. When his hooves got wet, the mud slipped off them, too.

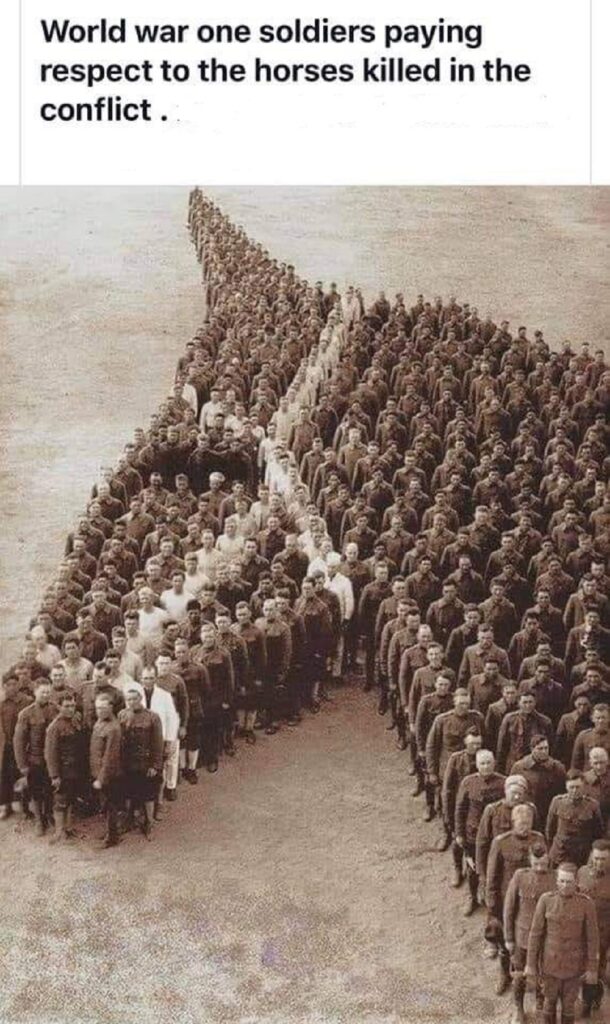

Mule was mute, but there was a way of telling what he was thinking – or at least what he felt. It was in the movement of his eyes, the way the muscles round his muzzle moved. It was clear he loved the Man who cared for him, clear by the way he pricked up his ears each morning when he came with the harness; by the way he nuzzled the Man’s shoulder as he prepared him for the day. Of course there was no way he could tell the man he loved him, but he wasn’t there for that: he was there to serve, and he served his master and the regiment well carrying a ton of danger on his back each day, making no sound and no protest as he struggled to follow his master and do his best to carry the burden, inside or outside the trenches, across the open fields exposed to the battle of men and the battle of rain and wind or snow blasting against him. The other mules would often stick their feet in the ground and refuse to advance, swishing their tails, slipping in the mud and starting at the explosions around them which fell from the sky. But Mule always remained calm. But it wasn’t the calm of indifference, though, and the Man loved Mule for that.

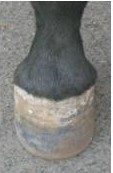

After a hard day’s work, the Man would crouch down at Mule’s feet with a pot of varnish, a special brush and a woollen cloth, and set about varnishing Mule’s hooves to enhance the black, white and grey pattern on the horn, painting and polishing every bit of them all the way round to under the fetlocks. He made Mule’s hooves shine. He took care to do this when the other mules weren’t there so as not to show his preference. He’d finish by giving Mule a pat on his neck behind his ear, there where he liked it.

Out of deference to his master, Mule was careful not to get his hooves dirty whatever the weather, whatever the constraints, whatever the long journey, lugging the heavy guns and bombs on his back or hauling them in the cart behind him. Sometimes, when the regiment ploughed through the large, never-ending muddy fields, there’d be noises ahead of them and men advancing towards them, men who looked just like his master but who wore different metal hats, some with points on the top, and those men fired bullets directly at them so that all the other mules shied and the guns fell off their backs or off their carts, and their men yelled. But Mule just stopped and waited until the Man told him where to go and what to do next.

The Man unloaded the bombs off Mule’s back or off his cart and hand them over to the regiment soldiers who put the bombs through a complicated machine which they set alight with a long stick which they first lit with another flame. They rushed back when the smoke started, covering their faces, some blocking their ears, and the bombs shot up in the air through the machine towards the men opposite, where they exploded in a cloud of smoke. The noise was earsplitting. Things came falling out of the air, landing with a bang around Mule and the regiment. But Mule didn’t budge; he watched it all happen, watched his master handle the explosives, hand out the gas masks to everyone,and sometimes fixed a mask on Mule and the other mule. The soldiers shouted, unable to recognize each other what with the masks and the mud splattered all over their faces. But Mule always recognized his master. It was the way the man moved, the way he never hesitated. the way he handled everything diligently, including his dying companions, signaling for a doctor, ensuring that each wounded man was well treated while they waited for the doctor to come, or at least for someone who knew how to treat them all properly out there on the field. And, when the Man finished what he had to do, he always came back to Mule. Mule stood still throughout all the battles, waiting for the Man to finish his duty and come back to him, while the other mules reared and kicked out, swirled round and round, straining their harness, trying to break free from their carts with the wheels stuck in the mud.

One day after the rain, when they arrived back at the fortress, the Man was unloading Mule’s cart. As he stacked the heavy guns and bombs in the cave, there was a sudden explosion. Everyone was blasted against the fortress wall and pieces of iron, stone and metal shot up in the air into a cloud of flying debris, and then fell. When at last it had all settled, everything fell silent and there was a mountain of smoking rubble, ruin and mud in the middle of the courtyard. Everything was grey; grey dust vanishing into grey slush. Even the sky was grey, and the silence was stronger than Mule’s.

Mule had been blown to pieces.

He’d been standing in the yard, waiting for the Man to come back to him.

The Man was alive, though, as were the other mules, and all the soldiers of the regiment who eventually went to lie in their bunks exhausted, each one staring up at the bunk above him, or at the ceiling, not hearing the rain fall on the debris outside, but still hearing the cracking and thumping of distant explosions out in the fields beyond.

But the Man couldn’t lie down. He couldn’t settle. He stayed up all night, searching in the soaked debris outside with his torch, the rain pouring down on him as he turned over the bits and pieces of iron, the shattered stones, the shrapnel and the mud, slipping, falling sometimes onto sharp points of steel, picking himself up, turning over more and more of the mess.

He found Mule’s leg just before dawn. He picked it up, took it into the cave and sat in a corner with it, wiping it with a chamois leather, even though there wasn’t much dirt on it. Nor was there any sign of blood. Perhaps the rain had washed it away.

But perhaps it hadn’t. He thought for a moment, looked closely at it, at the tell-tale marks. And then he brought out his pot of varnish, his brush and the woolen cloth. He started to varnish Mule’s hoof again, crouched up on the floor at the level where Mule’s hoof would have been had he been here with him still, which he was, in a way. He used precise, downward strokes with the brush, and as he did so he found himself thinking about the way Mule was, about Mule’s ‘spirit’, for want of a better word, wondering where it could be now, what it was, exactly. He surprised himself thinking like this, and stopped for a moment, brush in hand. Because never before in his life had he thought such things, about spirits, or whatever it was Mule had left behind inside the Man.

He waited for the varnish to dry, then buffed up the surface of the hoof with his woollen cloth. Then he took out his comb and ran it slowly through the light-brown fur, remembering the feel of Mule’s docile obedience, the nudge of his muzzle under his arm, the warm breath from his nostrils in the cup of his hands. He smoothed the coat down so it lay neatly over the top part of the hoof which shone beautifully with the varnish, more so than it had ever done before, and he thought: perhaps had he put more varnish on before and polished it up more carefully when Mule was alive, this would never have happened.

He went searching for a strip of leather and found Mule’s harness strung up on a branch overhanging the cave. This made him realize just how big the explosion had been. Perhaps that’s what it takes to make one ‘wake up’.

He began to tremble inside, something he’d never done before. Before, everything had been exploding outside him, around him, but now it was inside him, opening doors he didn’t know existed, onto things he’d never seen before.

He cut a strip from Mule’s thick harness and stretched it over the top of the severed limb then sewed it into the skin to protect the open bit at the top. Then he stepped outside, clutching Mule’s hoof. He nearly tripped over the shrapnel but managed to keep his balance and found a piece of metal which lay in the mud by the entrance and picked it up. The Captain was there, saying something about how lucky they’d been not losing any of their men in the explosion, but that he was going to get everyone from his regiment to check in case there was a dead body in the wreckage from another regiment perhaps, or indeed from the enemy camp, a body which may in fact still be alive, and they couldn’t risk that.

But the Man didn’t hear; not everyone listens to what they hear, and the Man was busy with something else. He needed to put into words what he felt. He had to write it down, here, on Mule, or what was left of Mule. He started to score into the leather at the top of the hoof. But the piece of shrapnel was a crude instrument to write with, so all he could put was: “Faithful Mule. Verdun 1916.”

Then he turned back to his other mules. The Captain was ordering all the soldiers out of their bunks to clear the yard. “There may be an enemy body in there. Find it,” he shouted then turned, pointing to the Man. “You too!”

The Man obeyed.

———–

A perfectly preserved mule’s hoof is on display at the Verdun World War 1 memorial.

___________________________________________________________

See also:

Mud and Massacre: Verdun 100 years on (for Armistice day)

Royal Jack and the Knight of Malta