Many are familiar with paintings and sketches of men in open boats on high waves hurling harpoons at giant whales. From the Japanese to the Basques, the British in the South Seas, the Norwegians, the Yankees, the Greenlanders – the list is long, we see lilliputian hurlers in agile skiffs circling the mountainous mammal with masted ships waiting behind them to help haul in the catches.

And well before these paintings, archaeological research of ancient harpoons and spear heads have shown evidence of whale hunting dating back to at least 3.000 B.C.

Why whales?

Whale products

Whale oil has always been in much demand: medieval Europeans used it for lighting and food, and as a lubricant. During and after the Industrial Revolution it was used for tempering steel, screw cutting and cordage manufacture. Miners used it for their headlamps. Baleen was extracted to make Buggy whips and Carriage springs, corset stays, fishing rods, umbrella ribs and hoops for women’s skirts.

Spermaceti – a liquid wax found in the head of the sperm whale – made the best candles, the light it gave being particularly bright, and continued to be used until the 1960s in the leather tanning trade, in cosmetics, the dress industry and typewriter ribbons.

Growth of Industrial whaling

It was the 17th century that heralded in industrial whaling. Onboard oil cookeries were introduced by the Basques, and quickly taken up by international fleets. This new introduction allowed onboard processing of the blubber to extract the oil rather than having to ship it all back to shore and lose precious hunting time.

By the 18th and 19th centuries the Industrial Revolution was underway and the demand for oil increased; technology was being refined. Whaling competition became fierce. Harpoon guns were introduced in the 1860s, followed by cannon-fired harpoons. The hunt for these leviathans was becoming more and more efficient.

According to Michael Clark, a California petroleum geologist quoted in The Arctic Sounder of June 2012, sperm oil sold for 1.77 dollars a gallon in 1856, and the US was producing 4-5 million gallons of spermaceti and 6-10 million gallons of whale oil annually. Steam-powered boats were soon equipped with cables and steam winches. By the 1920s breech loading cannons helped speed up the killings. In 1947 pistons were added to reduce recoil. Man had become so efficient with these killing machines that by the 1940s the world-wide mass destruction of whales was at its heyday. By the late 1930s, more than 50,000 whales were killed annually. Man was, paradoxically, now bringing on his own dilemma because soon the world’s stock would be depleted. The industry reached crisis point. Whales were now hard to come by. Alternatives needed to be found for oil and baleen.

Welcome in the oil industry… but that’s for another post. The above mentioned Clark is said to claim that the discovery of oil saved the whales.

International Whaling Commission

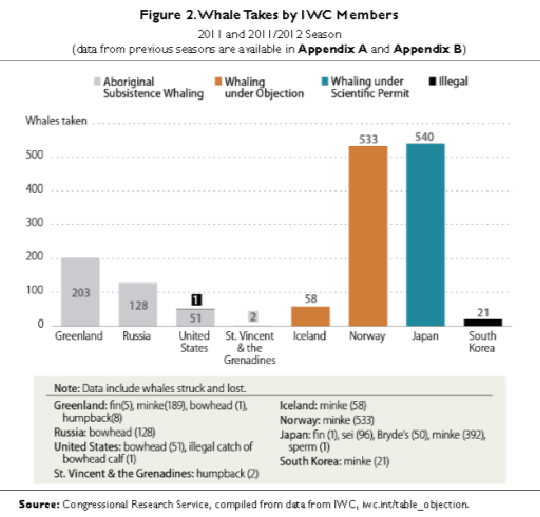

In response to the crisis, the International Whaling Commission (IWC) was created in 1946 and charged with the conservation of whales and the management of whaling. But continual elicit practices led to the introduction of a ‘moratorium’ on commercial whaling, in 1986, to help increase the whale-stock. To date 89 countries have signed up.

If commercial whaling has been banned by the IWC since 1986, it allows indigenous peoples to hunt under set limits. The United States: bowhead and gray; Denmark (Greenland): fin, minke, bowhead, and humpback; Saint Vincent and the Grenadines: humpback; Russia: gray and bowhead. The IWC sets catch quotas for this subsistence hunting over five-year periods. For the Bering-Chukchi-Beaufort Seas stock of bowhead whales taken by native people of Alaska and Chukotka, the limits for the period 2013-2018 were set at 336, with no more than 67 strikes per year (meaning a whale is hit but not harvested). By comparison, for the period 2008-2012 the catch limit for bowheads was 280 takes and 67 strikes per year.

Let’s go back to the Whale festival in Barrow, Alaska, where in the hotel, before the dancing and blanket toss, we had met with William. It turned out that it was William I’d seen out on the ice floe with his harpoon, friend, and umiak the night before. We chatted with William in the lobby of our central-heated hotel where many locals come to get warm, watch the TV and meet the visitors. William tells us he’d been out hunting for seals. “Yes, that was me you saw. There’s no quota on the number of seals we can hunt. We hunt them year round – the spotted seals,” he explains, his face dead pan, so unlike Spike’s agile expressions. Perhaps he was cold.

“And what about whales?” I asked him.

He belonged to the whaling crew in the village, he said. They hunt for bowheads during the season – late April to mid-May, and again in October. “53 bowheads caught in Alaska last season,” he affirmed with a curious shift of his shoulders which I interpreted as a humble manifestation of achievement. (This conversation took place after the chart giving figures above was published.)

“We push off from shore in umiaks,” William went on. “Only once you’ve harpooned the whale can you use aluminium boats. If you start with the aluminum boats the whales can hear them scraping on the ice so they escape us. They’ve got good eyesight, too. They can see the colour red, so we’re careful not to wear red.”

There were other ‘rules’ too, he said, but they’ve gone by the wayside. What rules? I pressed him. “Women weren’t allowed to sew or use knives during a whale hunt; some still believe this could cause the harpoon lines to break and get tangled up with the whale.”

He went on to explain how they camp out on the ice with their tents to watch for the whales. They have with them a kettle, propane gas – the wait can be long in the freezing cold – and a harpoon gun. When they’ve harpooned and killed the whale they haul it in to the edge of town away from the houses because the smell attracts polar bears.

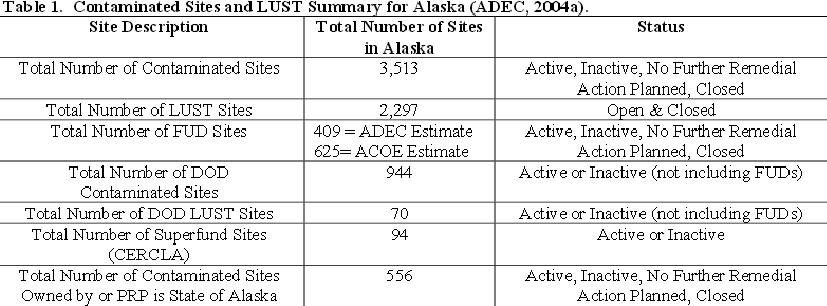

William’s propos didn’t wander on to the problem of toxic waste and contamination such as PCBs (polychlorinated biphenyl)*. Research on whales has shown several levels of poison in the meat (see chart below). I didn’t dare bring it up. Nor did I expand on the problem of whales and other sea mammals getting caught up in fishing nets and marine debris which – on a larger scale of whaling – is threatening the species, as is the noise pollution: Prudhoe Bay with its intensive oil drilling is only 317 kilometers (197 miles) away. Figures are difficult to come by, but here are some dated 2004:

Apart from the IWC, there are other, domestic, laws restricting whaling in the US, set by the Marine Mammal Protection Act (MMPA) and the Endangered Species Act (ESA). The MMPA prohibits all whaling except for subsistence use by Alaska Natives. Similarly, the ESA prohibits taking listed whales except for subsistence use by Alaska Natives. It can also restrict aboriginal takes where the harvest “materially and negatively affects the threatened or endangered species.”

Endangered whales in Alaska are: the Blue Whale, the Bowhead, Cook Inlet Beluga, Hump-back, Sperm Whale, Sei Whale, and the North Pacific Right Whale. See State of Alaska Department of Fish and Game.

___________________________________________________

* Polychlorinated biphenyl (PCBs) have been found in Alaska grey whales according to the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration; other pollutants are present in the Arctic environment and thus in the sea (more details in A Whale of a Time ). The IWC’s project Pollution 2020 aims to assess the risk to cetaceans from microplastics and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs). Read their report here.

Hump-back Whale

Humped Back in a huff and a puff you loll

bask in the waves sighing, pitching your tail

curling to hide some bad mood as you roll

over surface so still you tip, slide and sail

holding your breath

heaving your largeness away from our noisiness

as our boat turns in circles skimming the surface

unable to find you, trying to comprehend your meaning

as you shift away reeling camouflaged through swell

your world to us fathomless while we weave over waves

precarious – unsteady our restless world

while you beneath unfazed.