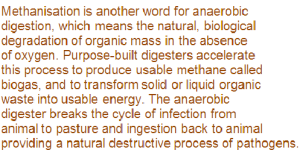

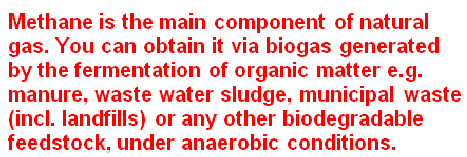

A messy subject, but important for our environment and economics. Manure is still massively under-exploited. Alone, it is a fertilizer full of pathogens which get spread back onto the fields. But put through a methane digester under anaerobic conditions and mixed with other biomass, 90% of those pathogens – harmful to animals, humans and plants – are killed, thanks to the high temperature level in the digester.

Harnessing manure to its full potential is a complex and expensive operation, but once set up and working it makes for a cleaner and sustainable environment; the overall health of herds improves since diseases are no longer lurking in the fields, and there’s no more need for anti-bacterial and anti-viral drugs – to which herds are becoming increasingly resistant. The meat we eat and the milk we drink is consequentially healthier.

Harnessing manure to its full potential is a complex and expensive operation, but once set up and working it makes for a cleaner and sustainable environment; the overall health of herds improves since diseases are no longer lurking in the fields, and there’s no more need for anti-bacterial and anti-viral drugs – to which herds are becoming increasingly resistant. The meat we eat and the milk we drink is consequentially healthier.

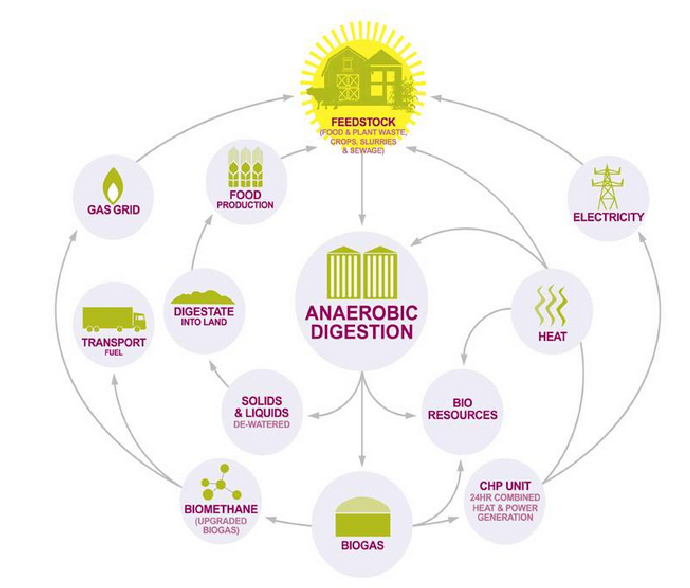

Methanisation concerns not just animal waste; the process is also used to transform other organic waste into energy, such as:

- municipal waste; grass cuttings, school cantine waste;

- agricultural waste – cereal grains, intermediate crops;

- agro-industrial co-products rich in organic matter: fat, fruit and vegetable scraps;

- sludge collected from the treatment plants.

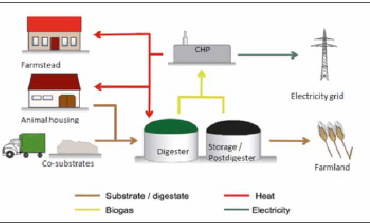

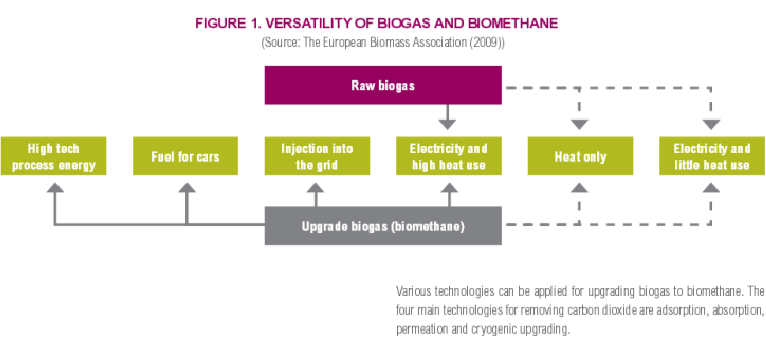

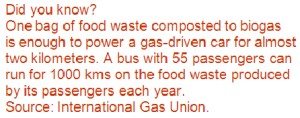

Anaerobic digesters contribute to cleaner land, air and water and consequently to the reduction of greenhouse gas emissions. The process also produces renewable energy, providing an alternative to toxic fuel energies such as oil, wood, or kerosene. The energy can be sold to the national grid; it can be used as fuel for agricultural machinery, for electricity on the farm and locally.

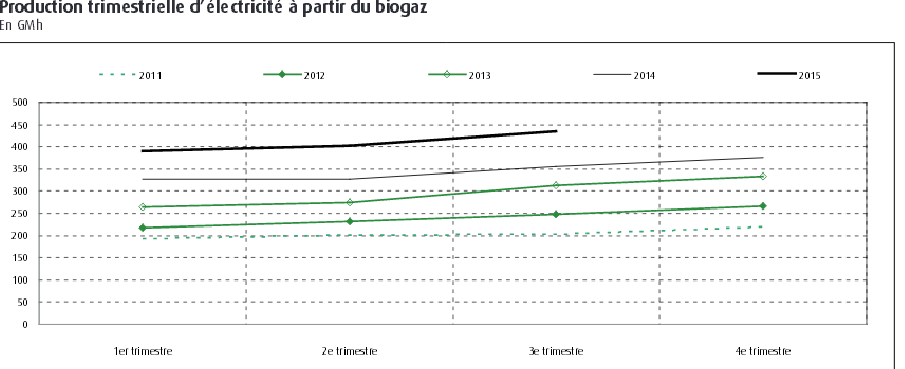

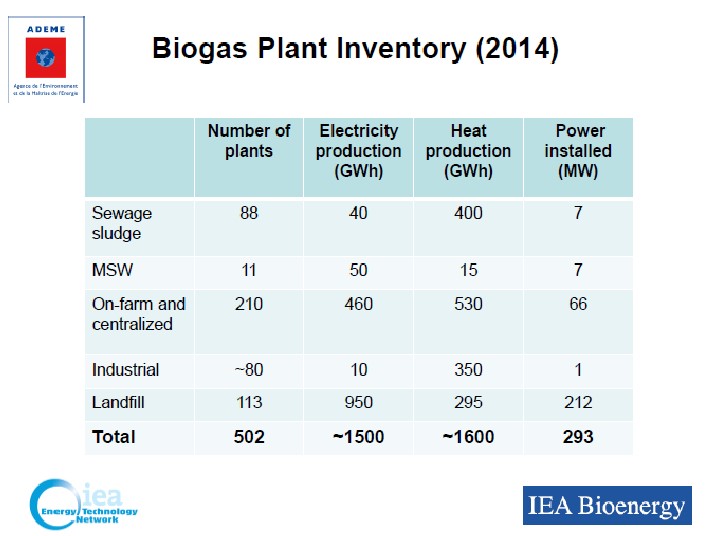

France lags behind other European countries when it comes to methanisation. Perhaps because it has relied  heavily on nuclear energy for power and the pressure to find energy alternatives has not been that urgent. But French nuclear installations are coming to the end of their lives; updating them to the next generation is an extremely onerous financial operation. Mind-sets are changing and, whereas figures show France is behind in the number of methanising plants, figures over the last two years have shown it has one of the highest growth rates of biogas production in Europe along with Denmark and the UK.*

heavily on nuclear energy for power and the pressure to find energy alternatives has not been that urgent. But French nuclear installations are coming to the end of their lives; updating them to the next generation is an extremely onerous financial operation. Mind-sets are changing and, whereas figures show France is behind in the number of methanising plants, figures over the last two years have shown it has one of the highest growth rates of biogas production in Europe along with Denmark and the UK.*

Biomethane, the French think-tank, and ADEME, the French Environment and Energy Management Agency, have been stepping up awareness in the country about the urgent need to increase and encourage the process, and are at present lobbying presidential candidates.

Near here, in Normandy, there are two installations, and it has taken time to allay the fears in the community where methanisation is not well perceived.

One of the farmers has a herd of 600 hundred cows. His digester uses manure, crop left-overs and other food waste – and more recently paper – representing some 30.000 metric tons of organic waste, all of which enables him to produce 1 MW of electricity per year. He sells this to the local grid (EDF) and uses some to heat his farm and run his engines. He has a 15 year contract to run the site which is co-financed by the EU within the framework of the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF).

When he set up there were complaints of bad smells; it seems he was spreading the treated fertilizer more frequently than regulations allowed and in areas not marked out for spreading. It was agreed by the regional ‘Préfet’** and the local council that paper waste could also be used in the digesters, since non toxic waste is acceptable within the French Environmental law***. However bits of bright blue paper have been observed in some fields after spreading; they look like bits of coloured packaging which makes one think of chemically treated book-covers and other glossy papers, all of which are toxic…

Bad practices soon lead to distrust, justified or not, in the methanisation system itself.

There was also the problem of the local roads being disrupted. Drivers had to be warned of the danger to children when driving the heavy trucks at high speed down the only road available as they transported the waste to and from the site, sometimes carrying up to 40 tonnes of waste. The road, not built to take such heavy loads, had to be repaired at at the cost of the local authorities and eventually a new purpose-built road was laid, again at the expense of the local authorities.

It is worth noting that the installation of the anaerobic digester was never questioned by villagers. Local authorities had accepted the proposition after putting it to the community. But reality changed opinions, and indeed some of the pursuant objections did seem to point to human error or – less kindly – to cutting corners, rather than the technology itself. Had there been honest, democratic exchanges between all concerned from conception through to completion, suspicions and fears could have been avoided on all sides.

But what about the farmers?

It is perhaps too easy to criticize the farmer. From his point of view – and that of all small farmers setting up – this system is expensive, complex, and highly specialized. Inadequate training can result in errors. Being strapped for cash can lead to the temptation to cut corners: for example, emptying cisterns in the open air which means smells escape. Bad odours can be reduced by re-sealing the gas containers, and also by choosing the right times and methods to spread the resulting biofertiliser.

In the end, the Regional Prefect was brought in to resolve the issues of non compliance to regulations and the situation was reported in the regional press. Now the operation is running smoothly. Meanwhile a proposition to install another methanisation farm in the region was taken to the local tribunal for similar fears of bad practices and disruption of local life.

Regulations

Unclear regulations, insufficient inspections and inadequate training prevent France from attaining the level of efficiency found in the rest of Europe, particularly Germany. Regulations are complicated, mostly because they are constantly changing and complex. The International Energy Agency (IEA) says clearer regulations, more joined up work and higher subsidies are needed to help small farmers. National governments in Europe have been giving more incentives to the big anaerobic digesters which are geared to electricity production, but not enough to small farmers for whom the system is complicated.

In France, regulations for installing methanisation digesters have been drawn up by the ministry for agriculture here. The ADEME also offers professional help for installing a methanisation plant.

This year the French minister for agriculture signed a charter of ‘good practices’ drawn up by the Union of French Methanisers: Association des Agriculteurs Méthaniseurs de France (AAMF), encouraging farmers to group together and exchange new innovative ways of methanising.

The French environment law specifies the manner in which bio waste should be returned back into the soil, and the EU Waste Framework Directive governing all EU member countries gives waste management principles concerning environmental nuisances such as odours. ****

The International Energy Agency has published recommendations on setting up a small scale biogas plant*****

Financing:

The IEA points out that generally, in its 29 member countries which include France, there is still a lack of awareness of the variety of funding sources available. In France, the ADEME offers subsidies for farmers. It is worth noting here that a French judge refused the continuation of the biggest methanisation project in France (Dijon) for lack of financial viability.

Who is responsible for inspections?

The French government guidelines on inspections published by the government indicate that all necessary controls be done by the developer himself along with his associates and the Prefecture. There seem to be no systematic inspections (I wait to be corrected on this, but have found nothing in my research). However, upon the request of the

Prefect (via local Councils who put forward a complaint) the ADEME and the regional councils (Conseils régionaux) will step in to inspect polluted installations.

French inspectors of « installations classées » (“classified installations”) were replaced in 2012 by « environment inspectors » who can verify and sanction reportedly bad installations. Click here for more.

How else to boost confidence in the community?

Returning to the above local problem above, it is clear that apart from adequate training for the farmer, funding and information exchanges, regular inspections with results made public would help boost confidence, because lack of stringent controls (as for pesticides, see Glyphosate) by competent bodies can lead to serious mismanagement which is damaging for everyone.

To address the problem of public confidence and excellence, a supporter of another more recent methanisation project in Normandy has suggested that the local community demand the farmer set up a business company for his project, open to neighbouring communities so that everyone can become shareholders. That way, the obligatory Annual General Assembly with votes from the shareholders would mean open exchanges of information and would give veto rights to shareholders. The shareholders would also benefit from a share of whatever profits the project makes. This would also make the shareholding local inhabitants aware of their responsibilities too, since many – dare one say – are die-hard complainers of any changes of the status quo.

Biogas statistics in France can be found on the government’s website here; Renewables in France, here.

Further afield

IEA’s Bioenergy publish country energy reports here.

The Global Methane Initiative: The Global Methane Initiative centralizes its 43 member country initiatives and experiences, sharing information on new technologies. France is not a member, but the EU is and encourages France to join. The GMI has an Action Plan for different sectors of methanisation which it shares with member countries, and gives guidelines for reporting from each country. Each member country reports on its own action plan – to be found here.

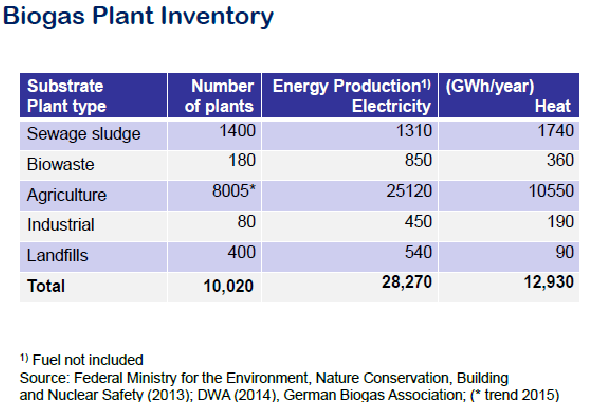

Germany: According to the IEA’s country report, Germany has by far the most biogas plants in Europe.

Sweden: according to the International Gas Union’s Biogas Report 2015, Sweden aims to have fossil free transportation in 2050; it aims to use 100% biomethane gas for industry by 2030, and 100% for the national grid by 2050. Sweden uses biogas as a vehicle fuel (there is growing interest in such countries as Denmark, Germany and South Korea).

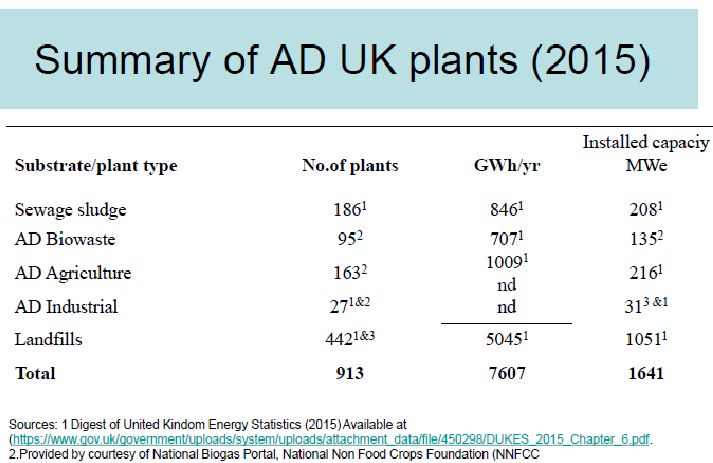

UK: the UK government has drawn up an Anaerobic Digestion Strategy and Action Plan.

USA: a detailed list of livestock digesters in the US can be found here. N.B. that statistics, the site says, are compiled from a variety of voluntary sources so may not be fully accurate. Regulations on anaerobic digestion and methanisation in the US are governed by the EPA – see https://www.epa.gov/anaerobic-digestion.

_________________________________________________

* p.14, International Gas Union Biogas Report.

** Regional Prefects are the representatives of the French Prime Minister and the government.

*** The French Environment Law (Code de l’environnement) defines toxic waste and gives guidelines of how to dispense of them here .

**** Article L.541-1 of the French Environment Law on methanisation can be found here ; EU Waste management principles can be found here.

***** “Small Scale AD”, Exploring the viability of small-scale anaerobic digesters in livestock farming, published by IEA Bioenergy, 2015. Available for free here.

Other links:

Association des Agriculteurs Méthaniseurs de France (AAMF)

European Biomass Association

Information on French inspections of polluted site in Normandy can be found here; and here.