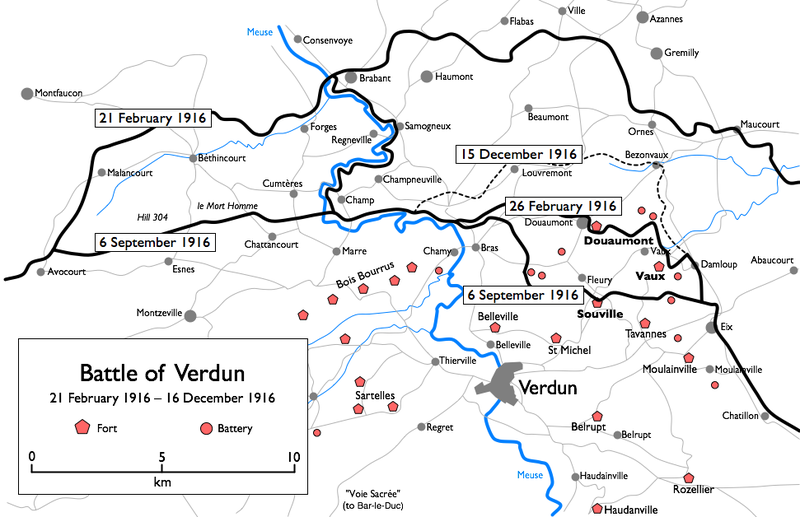

France and Germany come together today, 29th May 2016, at Verdun to commemorate the centenary of the longest and one of the fiercest battles of World War 1, the Battle of Verdun. After 300 days, it left 163 000 dead (French and German) and 370 000 killed, injured or missing. Fear, mud, rats, corpses – human and animal -,deathly explosions, poor visibility, and cold dread accompanied the sheer brutality of the onslaught from the enemy. German soldiers were under the orders of General Erich von Falkenhayn who declared he wanted to ‘bleed France’ and chose Verdun where there were no English soldiers present (they were further north) – the English were feared more by the Germans at the time.

“Do not forget us”, the last surviving Poilu* pleaded the Verdun memorial committee in 2008.

It may come as a surprise that the Nazis were the first to propose an international commemoration of the battle of Verdun, in 1936. The war in Spain was about to erupt; France was desperate for peace and accepted to participate. The Olympic Games were to take place in Berlin. At the ceremony the delegate for the Nazis proclaimed their belief and hope of peace between France and Germany.** Meanwhile Hitler was already re-arming.

In 1966 President de Gaulle commemorated the 50th anniversary of Verdun, without Germany, but expressed his desire that one day Germany and France could commemorate together.

In 1984, President Mitterrand and Chancellor Helmut Kohl, at a commemoration of all those who died in WWI, famously joined hands in front of the memorial as a mark of reconciliation.

Today, to mark the 100 years since the terrible battle, German Chancellor Angela Merkel and French President François Hollande are together at Verdun for a joint commemoration.

A grim reminder of this tragedy still lurks underground. Toxicity from buried war debris and dead bodies is still polluting the earth in areas now labelled “Zone Rouges”, contaminating crops and farm produce: last year alone an estimated 150 000 euros-worth of milk was destroyed around Verdun, cows went to slaughter because they’d been grazing off the grass, and cereals were destroyed***. Lead and cadmium has been detected in wild boar in the region and, even if no tests have been carried out recently, water is still suspected to be contaminated.**** Over nine hundred million shells were used in the battle of Verdun, but 30 percent of them didn’t explode and much still lies rusting in the ground. In 2015 alone, 50 tonnes of munition were taken away from the Verdun Forest by the Service de Déminage of Metz*****. Hundreds of tonnes of this debris are destroyed every year; to date 275 tonnes of toxic debris are being stocked, scheduled for destruction next year.

The following story was inspired by an unusual exhibit I saw in the museum during a visit to Verdun. It is in memory of all those who fought in the Great War.

MAN AND MULE

There was a man who loved his mule. He stabled it in a natural cave, next to the ammunition store he and his regiment had built together in the forest behind the fortress. In fact he had five mules in his care, but Mule was his favourite. Mule’s hooves never got dirty, whereas all the other mules’ hooves would be smothered in mud; yet Mule worked just as hard as the others, pulling the laden carts over the uneven earth, carrying the regiment’s artillery to where the next battle was to take place, or to where they decided it was safe to stock it. When the rain slashed down and flooded the trenches, the other mules would skid and some would even fall and their fur would get caked with mud. The mud stuck to them, and when the sun came out it dried on them so that by the end of the day it seemed they were wearing grey shrouds. But Mule never had such a shroud because he seldom fell, and when he did he’d just shake his coat and the mud rolled off. Likewise, when his hooves got wet, the mud would slip off them, too.

Mule was mute, but you could tell what he was thinking, or at least what he felt, by the movement of his eyes and by the way the muscles round his muzzle moved. It was clear that he loved the man who looked after him, clear by the way he pricked up his ears each morning when the Man came to put the harness on him; by the way he nuzzled the Man’s shoulder as the man prepared him for the day. But he couldn’t tell the man he loved him: he wasn’t there to say it, he was there to serve, and he served his master and the regiment well, carrying a ton of danger on his back each day, making no sound and no protest as he struggled to follow his master and do his best to carry the burden, inside or outside the trenches, across the open fields exposed to the battle of men and the battle of rain and wind or snow blasting against him. The other mules would often stick their feet in the ground and refuse to advance, swishing their tails, slipping in the mud and starting at the explosions around them which fell from the sky. But Mule always remained calm. It wasn’t the calm of indifference, though, and the Man loved Mule for that.

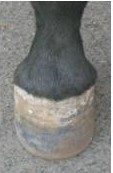

After a hard day’s work, the man would crouch down at Mule’s feet with a pot of varnish, a special little brush and a woolen cloth, and with much care would set about varnishing Mule’s hooves to enhance the black, white and grey pattern on the horn, painting and polishing every bit of them all the way round to under the fetlocks. He made Mule’s hooves shine. But he always made sure that he did this when the other mules weren’t there so as not to show his preference. And then he’d finish by giving Mule a pat on his neck under his ear, there where he liked it.

And, out of deference to his master, Mule was careful… read on here.

*Poilu: literally ‘hairy’ – an endearing name given to WWI French soldiers who had little time to shave off beards on the war field.

** Le serment de Douaumont, 1936, quoted in Le Figaro

*** L’Est Républicain

**** Mediapart

***** Ouest France