The fall-out from the spectacular explosion of the chemical factory Lubrizol near Rouen in France on 26th September not only nearly asphyxiated local inhabitants with clouds of soot swirling in the air: it has since infiltrated the soil and water tables for hundreds of kilometres in the north of France. Lubrizol makes lubricants and petroleum additives for engines, in particular large lorries, buses and ships.

Emphasising the need for transparency, the government has made available online a list of products which escaped in the explosion, admitting they are potentially “mortal if penetrated into respiratory organs”. More toxicity is feared from those products which – because of the explosion – got mixed with a panache of other substances in the stock: the cocktail effect.

I spoke to my friend in Rouen the day after this terrible accident. “Rouen is a ghost town,” she told me. Restaurants, shops, schools and the university where she teaches had closed down. Everyone was told to stay indoors.

You must wear a mask, I said, not knowing that the pharmacies were already distributing paper masks to the population – something my friend said was almost a joke, they were so thin. The smell was nauseating, people were coughing and spluttering.

At the time it was still not known exactly what was in the air, but now the Prefecture of Seine Maritime has published online the list of the 5 262 tonnes of chemical products which burnt and escaped into the air. (figures have since gone up. ed.)

The dark cloud over Rouen gradually turned white, my friend informed me, as particles of asbestos roamed around in the air with all the rest of the toxic waste.

Asbestos? In our village north of Rouen we had to change our roof years ago at large expense (ours) in order to respect the law because of asbestos in the tiles. The Lubrizol factory still had asbestos in the roof? Note that the factory was inspected at the beginning of September, not even a month ago.

The Prime Minister, quick to step in after the disaster, went to Rouen and promised transparency on what had happened, trying helplessly to placate the untrusting, sceptical inhabitants – not only in Rouen but all over the region – by saying analyses of toxicity levels are ongoing.

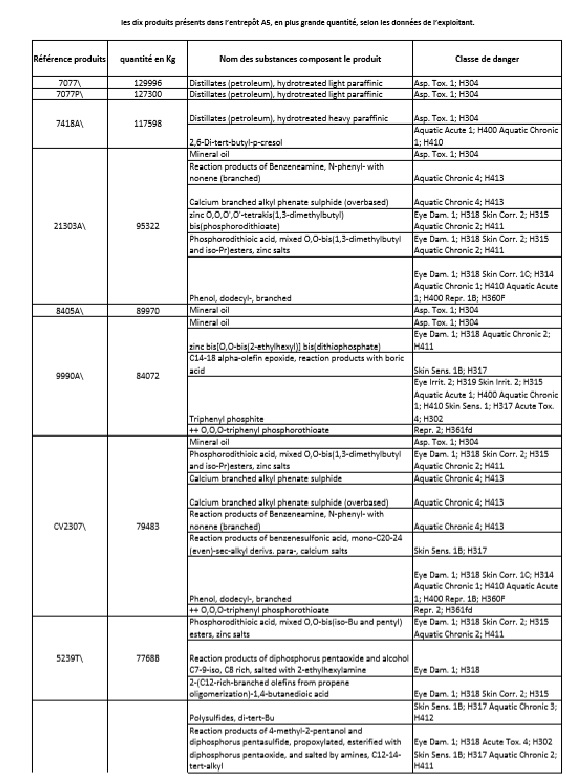

Government online information shows that corrosive substances and irritants, some cancerous and all toxic for the aquatic environment, were released during the explosion. Take a look at the list of products and their danger levels, which blew up in stockhouse A5. List according to control data.

The environmental organisation Robin des Bois, well renowned for its expertise in dangerous products, reports that these substances not only ended up in the urban streets of Rouen, but fell into the Seine which runs through the city and away… Fall-out has since spread all over the Seine-Maritime department with its endless rich agricultural and pasture fields and on to other departments farther afield: the Oise, the Somme, The Aisne, the North.

The 3 products present in the highest quantity (129, 127 and 117 tonnes) were petrol distillates which are cancerous according to the European Chemicals Agency ECHA. Security risks in the other exploded products are listed as “very toxic for aquatic organisms, provoke serious ocular lesions, and provoke skin irritation.”

479 security risk notices of these products were also published on the website of the Prefecture of Seine-Maritime Department, showing the high risk of combustion. Danger depends, according to the Prefecture, on the quantity of toxicity present, and how the molecules will turn after having burnt, and how it has been exposed (skin contact, inhaling, ingestion).

My friend escaped to Dieppe for the day to breathe the sea air and get away from the smog and the smell and avoid the migraines and nausea the cloud was causing in the area. But the ghastly reality is there, unescapable and this is just the beginning of the toxic spread…

And what about the farmers, consumers, and the circular economy?

This is a tragic disaster for farmers in the region, already reeling with the losses incurred by the punishing droughts this year. And it’s consequentially a disaster for consumers up north who have been encouraged to eat local products in the interests of a circular economy. Farmers from the Seine-Maritime department have been obliged, by order of the Prefect, to stop producing and to keep their stock under wraps while awaiting official results of analyses since the soot swept over vast swathes of agricultural land. Cows were brought into barns (Mayors advised). Another Prefectoral order forbids 112 communes in the Seine-Maritime from selling any agricultural products, be they beets, corn, potatoes, or eggs, while analyses are being done, particularly on corn. Departments further afield are under alert: the toxic cloud covered another 40 communes in the Oise, 39 in the Somme, 14 in the Aisne and 5 in the Nord et le Pas de-Calais departments, according to the agricultural Unions FNSEA and Jeunes agriculteurs.

700 000 litres of milk per day lost

For the farmers, the main problem about stocking these products while awaiting results has been for milk. Whereas stocking fruit and vegetables and eggs is do-able for 28 days, milk can only be kept for three days. To date, since the accident, 500 dairy farms have had to stop production and stock their milk which will have to be ‘thrown out.’ Stocking costs money. According to the milk industry, an average of about 700 000 litres per day is being lost since the Lubrizol explosion.

There is the added of problem of how do farmers eventually get rid of the contaminated products? They obviously cannot tip it into the soil. How much money will it cost them to dispense of their contaminated products, they ask. Will there be government help? The Prime Minister has promised that all farmers will be compensated. In what way exactly? French farmers – the French everywhere – are wary of mealy words from politicians and demand more precise decisions. The French Dairy Interbranch Organization CNIEL has just announced it will pay farmers to help them stock the milk while they await compensation promised by the government, urging that such compensation be quick to arrive.

Less rigorous regulation

France has been less rigorous these last few years in its regulatory procedures concerning Seveso classified industrial installations. Seveso is the legsilation on the prevention and control of dangerous chemical accidents, in force since the 1976 major accident in Seveso. It has been reported in the specialised press that the Prefect of the Seine-Maritime Deparment, taking advantage of the French government’s loosening of restrictions, allowed Lubrizol to increase its stock capacity for those very same dangerous products which were at the origin of the industrial accident.

- June 2018: the government reduced the list of projects which would normally require environmental evaluation.

- August 2018: the law Essoc handed over responsibility to the Prefect (as opposed to an independent environmental authority, which happened before) for existing installations which require modification (as opposed to new installations being built). The government would like to extend this passing over of authority through a new energy-Climate law coming soon. (Note the mention of ‘droit à l’erreur’ – ‘the right to make a mistake’, in this law).

Lubrizol took advantage of this relaxing of regulation. It is reported that Lubrizol made two requests to increase their stock of dangerous products, on 15 January and on 19 June 2019. As permitted by the new law Essoc the Prefect gave his permission, but not the independent environmental authorities. In both cases, it was considered that no environmental evaluation was needed. The Prefect still does have the right to request a new environment risk study, but has not yet shown that it requested such a study.

- Just 3 days before the accident, the Prime Minister announced the government’s plan to simplify rules and regulations for setting up industrial plants, in order to accelerate industrial projects in the region, including allowing work to start before… receiving environmental authorisation.