‘Base muleteers of France… dare not take up arms like gentlemen!’ (Shakespeare, 1 Henry VI, III.ii.68.)

Mules and muleteers have played a key role in the world’s economic growth; without their hard work, stamina, strength, and patience over hundreds of years prior to mechanization, much of the modern world would not exist: they helped to construct it.

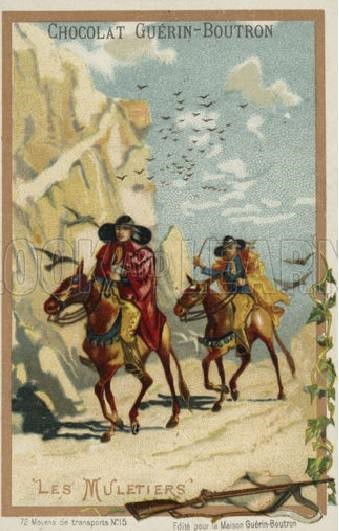

Yet they have been the butt of jokes for centuries, and denigrated by many, including Shakespeare. Indeed, in 19th century France muleteers were known as a foul-mouthed and ribald crew.

But these tight-knit traditionalist travelers were a colourful bunch as well; they ‘wore pigtails well into the 1830’s, a red wool bonnet (which they did not even remove in church) under a large hat, gold earrings, a red waistcoat and a neckerchief, a white serge jacket studded with copper buttons, and green serge hose. Bedecked with pompoms, tinkling with bells, the pack-mules were as dazzling as the muleteers; and in many villages and small towns, in the Cevennes … a mule train passing through was one of the few distractions of the time.’ (‘Peasants into Frenchmen’, Eugen Weber).

These muleteers grazed their beasts in people’s fields as they journeyed across the landscape, bearing loads of up to 240 lbs per animal – twice as much as a donkey – taking, for example, sacks of coal to provide heating during the cold winters, carrying food, wine, water and whatever else necessary for the livelihood of communities, ensuring trade both nationally and internationally.

The Pre-industrialization Machine.

Mules shaped our modern world. Through purpose cross-breeding, they were ‘designed’ by man to provide the only reliable means of transport across huge expanses of land before the laying of roads and railroads. They were the pre-industrialization machine. Without them, how would the gold, salt, silver and other mines have fared if they hadn’t been there to transport it all to the coasts for international trading which boosted money markets? Everywhere and anywhere they helped lay roads, railways, telephone lines, dams and canals. How would the preparations for the Panama Canal have been carried out without them? How would WW1 have panned out, where they were indispensable for transporting cannons, ammunition and provisions, and for carrying the sick to safety over muddy uneven terrains which no other vehicle was able to safely negotiate?

Cross a male donkey with a mare and you get a mule (cross a female donkey with a stallion and you get a hinny, often referred to as a mule). Mules are nearly always sterile due to the particular structure of their chromosones. These beasts were in demand over horses as a working animal because they are tougher, with hooves much harder than those of a horse; a mule needs less to eat, needs less sleep ( just 4-5 hours), and unlike the horse, he has the endurance of a donkey. Being a hybrid, he is less nervous than the horse, less stubborn than a donkey and capable of carrying much heavier loads than a horse can for a longer period of time (managing 300 lbs for up to 7 hours a day).

A Sussex university study has shown what owners have already known for centuries: that the mule is more intelligent than the horse, which means it understands its master more easily. He is thus easier to train. And he is patient, friendly, and enjoys affection. He is also a smoother ride than a horse. Yet he has the reputation of being in a kind of ‘lower cast’ than a horse, even if he serves man better. Once again, in Coriolanus, Shakespeare debases him, along with camels, in Brutus’ words:

‘…he would/Have made them mules, silenced their pleaders…

… holding them…

Of no more soul nor fitness for the world

Than camels in the war, who have their provand

Only for bearing burdens, and sore blows

For sinking under them.’ (Coriolanus, Act 2, Scene 1)

France

It is a paradox that man sometimes spurns what he has made. And indeed man has ‘made’ these hybrid animals. Take France, for example, where mule breeding became a lucrative international trade. King Louis XIV’s administrators encouraged mule breeding during the 17th century where the animals were bred in the rich pasture land of the Auvergne – stud farms were in the Planèze region between Saint-Flour and Murat. In fact many of the mules originated from the fertile Poitiers region where the mule poitevine was being bred by crossing a mare draught horse called the poitevin mulassier with the famous baudet du Poitou.

These poitevin mules were sent to the Auvergne at the age of 9-10 months and eventually sold on the markets in Saint-Flour, Puy-en-Velay, Maillargues and Allanche to Spanish traders, to buggy merchants in Lyons and to the Languedoc. They carried silk and barrels of wine to Saint-Etienne, Roanne wines to the Auvergne plateau and Le Puy. In the Midi, where roads were not suitable for wheels, they transported oranges, lemons, olives, anchovies, wine, figs, and grapes to far flung villages and markets over long distances of rocky and road-less landscapes.

In fact trade in mules in France had been going on for centuries. From the 14th-15th century the regions of the Haute-Auvergne, Languedoc and Béarn were selling mules to Catalonia along with horses; the main mule and horse trading centre was in Rouergue.

Later, in the 18th Century, mules were sold and bred in the western part of the Ariège; in Toulouse mules were preferred to the more fragile horses; likewise in Provence, and in the Jura (Arinthod, Bourgogne-France-Comté) where mules fetched higher prices than horses.

But the real hey days of the Poitevin mulassier trade for ‘mule-making’ were from the middle of the 19th – mid 20th century. Today the Poitevine mule works in forestry.

Spain, the Americas and The Knight of Malta

Christopher Columbus took jacks and jenny donkeys over to America to reproduce mules which, amongst other things, helped the Conquistadores conquer the Aztecs. More donkeys were brought over from Cuba ten years later for mule breeding in Mexico. The females mules were ridden while the males worked in the silver mines and helped guard the Spanish frontier.

Come the 18th century, breeding mules was a flourishing industry in Spain (and Italy) as well as in France. Whereas for many years Poitou in France was the primary European breeding centre (where around 500.000 mules bred each year), Spain soon took over to be at the forefront of the mule-breeding industry as Catalonia and Andalusia each developed a larger and stronger breed of donkey.

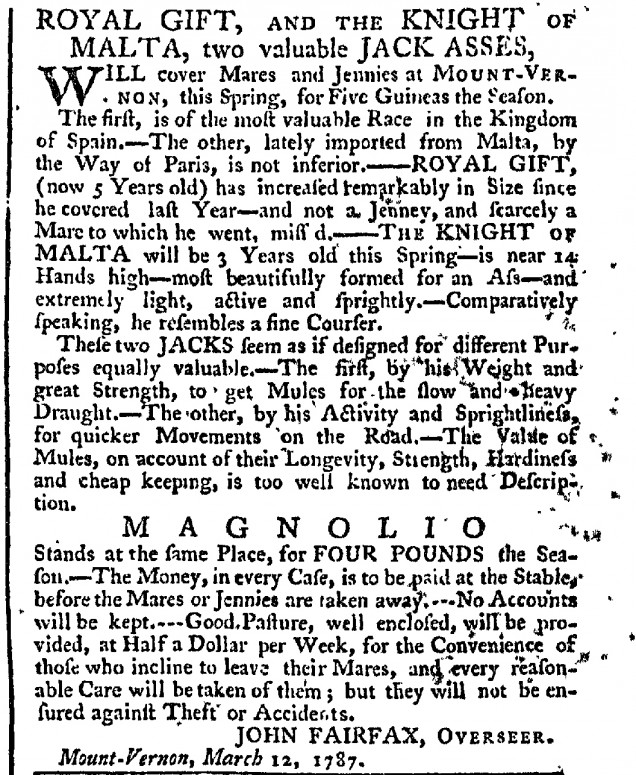

In America, George Washington, seeing the potential of the mules working in the mines, took a keen interest. He wanted to breed an even tougher beast and, recognizing the robustness of the Spanish donkey breeds, in 1787 he turned to King Charles III of Spain. The Spanish king, proud of the Spanish stock (some imported from France), had previously banned the export of these animals but made an exception and sent a ‘Royal Gift’ of two jacks and three jennies. One of the jacks – an Andalusian donkey – was named ‘Royal Gift’. Thus the American mule business started in the late 18th century.

A few years later the Marquis de Lafayette sent Washington a black Maltese jack donkey which they called ‘The King of Malta’ who arrived along with some jennies to be crossed with the Spanish stock and the ‘compound’ mule was born: stronger, hardier and costing three times as much as a working horse.

Thus the hardy mule was well set in America, working in the tobacco and cotton fields, pulling wagons westwards in harsh conditions… More and more donkeys were imported from Spain for breeding. During the decade 1850-1860 the number of mules in the United States rose 100%, and by 1897 with the cotton boom and the Gold Rush, there were over 2.2 million mules in the U.S.. A mule by then was worth 120 dollars (roughly 3.000 dollars today); they were not only working on the cotton fields, in the silver and gold mines, they were hauling the newly found borax in the extreme temperatures of Death Valley.

In more recent U.S. history we find them in China during the China defensive of WW11*, and again in extreme conditions in the jungles of Burma with American fighters, and in Korea in the early 1950s. The U.S. bred and sold mules to the Mujahidin fighting back the Soviets in Afghanistan in the 1980s. Today the Marine Corps Mountain Warfare Training Center, in Bridgeport, California, offers a course in using pack animals in war to American and foreign military personnel.** Mules are also bred and used by the U.S. Forestry service to resupply fire lookout towers and assist with trail maintenance.*** They are at present replacing horses as more comfortable ride for those with minor physical deficiencies. Finally, the growth of the U.S. Amish population has led to the increase in sales to that community.

The Rich muleteers of Panama

During the colonial period, muleteers in Panama were rich profiteers in cahoots with property owners and rulers. They held the monopoly in trade routes – basically mule routes – their mules assuring not only transport to and from the silver mines but all transport across, into and out of the country. However, the climate in Panama was not favourable for breeding and they were imported from other countries such as Nicaragua, El Salvador and Honduras – numbers of those imported leveled to 1.000 per year in the middle of 17th century. But their feed – particularly on the north coast where corn didn’t grow as well as in the south – had to be imported. All these extra expenses meant that the cost of mule travel shot up to a level well above any of the neighbouring countries. Rebellion against the Spanish colonial authorities there, and from other sectors including the English, contributed to the breakdown of the muleteers’ stronghold.

Then came the scramble for the digging of the Panama Canal in the 19th century. Roads had to be laid first, for which the mule once again was essential. Both the U.S. and the English, after the French, were seeking rights for the Canal and a certain Colonel Charles Biddle in the 1830s negotiating for the U.S. managed to make his way into the Panamanian elite to clinch a deal, but once there and setting up the plans he came face to face with fierce opposition from the nationalistic Panamanians and made many enemies, including the Americans since he failed to obtain a canal concession. He was loathed by the Panamanians who, when he left defeated, offered him some low grade silver for his expenses. This made him furious and he wrote to them “If you will insist upon my carrying such adulterated trash as this to Cartagena, be so good as to furnish the necessary number of jackasses for its transportation.” (He was finally compensated in gold.)

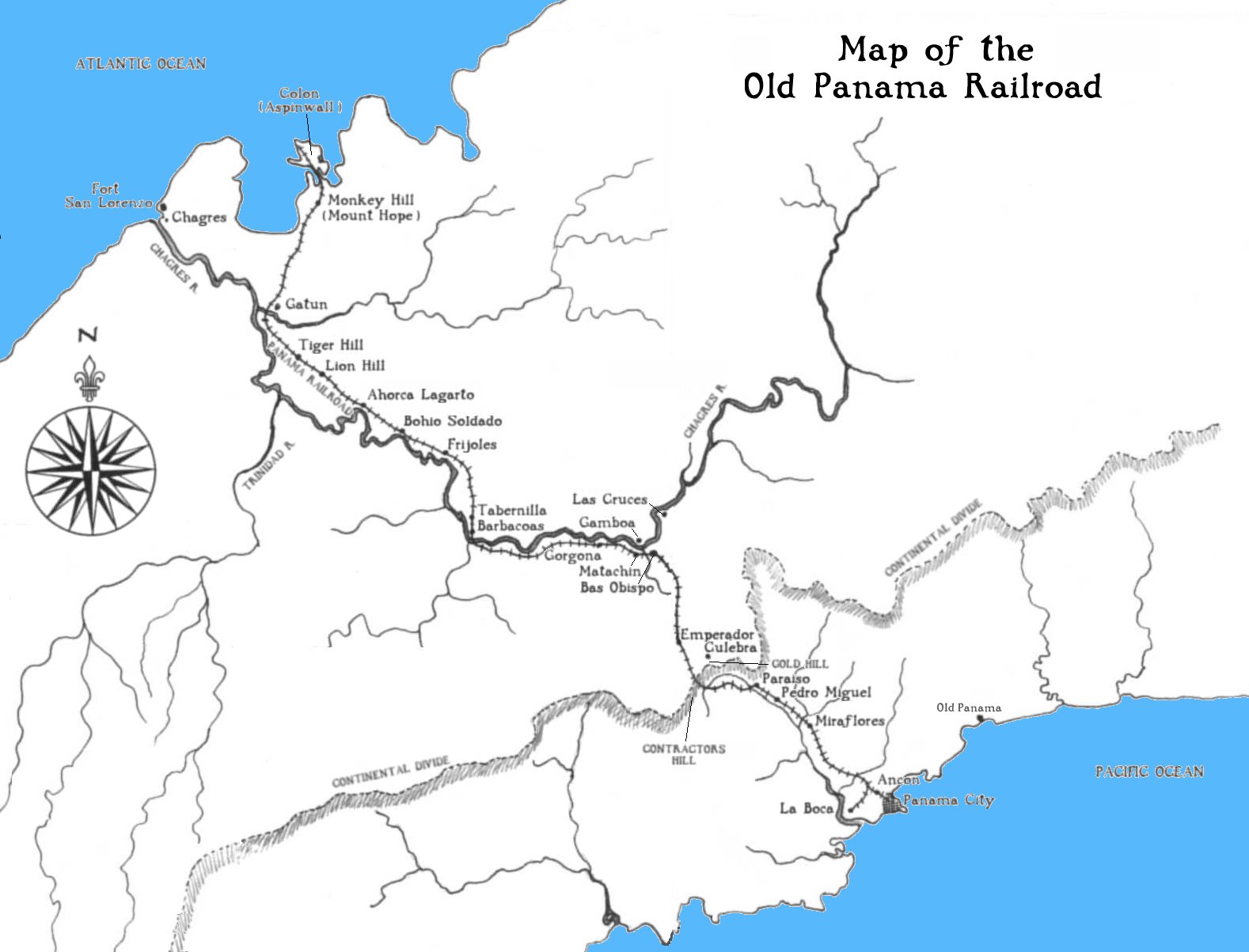

Later, the Panama Railroad Company was set up in 1849: its American vice president was the famous Latin American explorer John Stephens, who fell off his mule and injured himself seriously on his way to Bogota to support his friend Aspinwall in the signing of the Agreement for the railroad with the new government. The mule surely went on to accompany his brothers and sisters in laying that very railroad (see map).

Coffee, sugar, Brazil and South America

Mule transport played a predominant role in the economic success of central Brazil in the early 19th century. Mules were the main means of transport in the coffee producing regions of south central Brazil where canals and railroads were not yet laid (due to financial and political instability). As coffee exports increased, so did the demand for mules and the price they fetched. Intensive mule production in the area followed. It was these mule troops (‘tropas’) which opened up the tracks for the railroads linking the interior mining, coffee and sugar producing areas to the coast, the coffee market using the trails the most. As trade increased, so did the market for mules. Some were illegally imported from Uruguay and Argentina. (Argentine traders were also common Bolivia, where the trade was lively). Transit taxes in Brazil were imposed on muleteers passing through towns after or before being sold. After the railroads to the coast for export were laid, mule numbers declined.

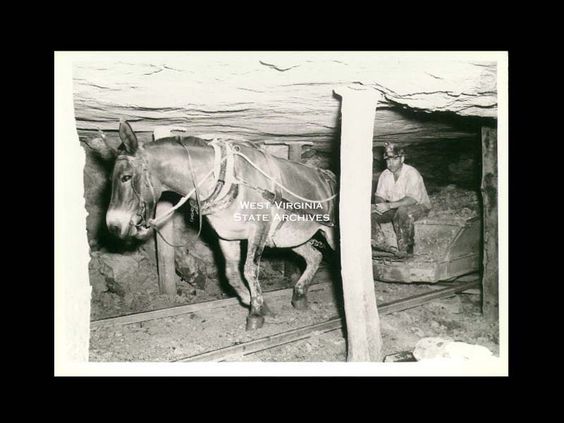

England: shave their legs

Mules hardly seem to figure much in English history prior to WW1 (anecdotes welcome), in comparison to other countries. It has been suggested that the English associated them with Papists and extreme poverty and, since the English rejected the Roman Catholic faith after Henry VIII, they had an ambivalent attitude towards the animal. But this didn’t stop people from using them in the 19th century in the coal and copper mines and other factories alongside the more documented Pit Ponies.

However, they weren’t ignored when it came to war. The mules came into their own for the British at the beginning of the 20th century where all prejudices were knocked away by sheer necessity and fear in face of a full-blown World War. Those working in the mines were lifted away and shipped to the continent to serve in France, Gallipoli, Egypt, Basra…. At the start of the Great War the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) had an army of 25.000 mules and light draught horses in France alone; at the end of WW1 they numbered 475.000.

The entire WW1 horse and mule force working for the British and Commonwealth forces throughout the world amounted to 1 million by the close of that War.

256 000 of these British mules died on the Western Front as a result of shelling, bombing and harsh conditions, and also because the soldiers in charge of them knew nothing about how to care for them. They had to learn ‘on the job’ while shells were flying and the weather worsened; orders were often confused and constant relocation to ad hoc hiding places added to the chaos. The first year horses and mules were shaved in winter to discourage parasites and skin diseases which tended to spread when the animals were stabled close together. Many died of exposure as a result. Having learnt their error, the troops from then on reduced the clipping to the legs only.

Earlier In 1905, the British were using mules in India where a regular corps of mules, camels and carts was set up: there were 21 Mules corps. They carried guns and ammunition alongside the soldiers in the North-West Frontier war. ****

Cyprus

Cyprus’ biggest contribution to the Allies in WW1 was mules and muleteers: 120.000 were bought – by force – from Cypriot owners by the British Army. The beasts were requisitioned, the owners paid in compensation, or threatened with prison if they didn’t comply. These mules made up the British Army’s Macedonian Mule Force which fought in Salonika, transporting supplies and the wounded. Muleteers were needed too; the British War Office requested 3.000 muleteers to help fight the German-Bulgarian army at the Macedonian Front. A 15 day basic training was offered for them in Famagusta and elsewhere; nearly 12.000 Cypriots were trained and recruited, most of them Greek Cypriots (89%, 11% Turkish Cypriots).

Between 1916 – 1919, 6% of Cyprus’ population were enlisted as muleteers, a total of 15,910 men. At the end of the War, these muleteers serving in the British Army were awarded 3.000 bronze British War Medals by the Cyprus government.***** After the armistice, the Cypriot Mule Corps went on to serve in Istanbul.

New technologies, mechanization, and the return of the mule

Mules were saved from their life of drudgery by mechanization. Whereas industrialization profited at first from their hard work which contributed greatly to the making of the modern world, the new ensuing mechanization, new roads and railways which they helped to lay in the 19th century brought on the beast’s decline in numbers. Carters to shoe horses rather than mules replaced muleteers, and the number of horses rose along with the number of carriages and buggies.

Whereas the mule’s return in force came with the grand-scale wars waged by man in the late 19th century and the 20th century, he is no longer in much need now that the nature of war has changed, bringing in new machines, both flying and terrestrial.

However, the mule is back at last back again and this time in a more peaceful way, recognised for his talent and attributes through Associations which show just how capable, beautiful and good a mount he can be. See, for example, the activities of the American Mule Association, the French Institut National Ânes et Mulets and the British Mule Society. They are also present in the tourist trade, but vigilance is high to save the animal from the arduous labour and suffering his ancestors went through. There are many people who care about their welfare through Associations, monitoring and striving to prevent abuse and maltreatment – which often comes with poverty. Take for example The Brooke: Action for Working Horses, Donkeys and Mules, present in Africa, Asia, Latin America and the Middle East. And mules are still bred – as mentioned above – for pleasure riding and for help in the forestry service. Because this animal can be a very faithful friend and worker. As one owner said: once you are into them, it becomes an obsession, they sort of ‘get to you’. Last week’s story shows just how symbiotic a relationship can be between a man and his mule. And history shows just how much the mule has contributed to creating the world we live in today.

___________________

Sources:

The Big Ditch: How America Took, Built, Ran, and Ultimately Gave Away the Panama Canal. Noel Maurer and Carlos Yu. Princeton University Press, 2011.

Down in Panama. M. Guinn, Annual Publication of the Historical Society of Southern California and of the Pioneers of Los Angeles County, Vol. 6, No. 2 (1904) University of California Press on behalf of the Historical Society of Southern California.

Economic Change and Rural Resistance in Southern Bolivia, 1880 – 1930, by Erik Detlef Langer. Stanford University Press, 1989.

L’engouement pour les mulets, Jean-Marc Moriceau, Pôle Rural-MRSH-CAEN.

The Market for Mules in Brazil 1825-89, Herbert S. Klein. Academia.edu.

Peasants into Frenchmen: the Modernization of Rural France 1870-1914, by Eugen Weber. Stanford University Press, 1976.

FirstWorldWar.com – a multimedia history of World War One.

American Mule Museum.

U.S. National Park Service

* Footage of China Defensive WWII here

** The New Yorker

*** See http://wildfiretoday.com/tag/pack-mules/

*** Click here for a short entertaining and informative account of mules in the Indian Infantry.

***** Cyprus’s Non-military Contribution to the Allied War Effort during World War I, Antigone Heraclitou, Open University of Cyprus, 2014.