According to scientists, glyphosate can be toxic: it is a question of measure, dosage, and the mixture with other molecules. Using safe dosages is a very delicate balancing act and questions arise as to whether we should risk keeping such a product on the open market. Before we complain at such radical farming treatment, take a look at what we do in our gardens. To eliminate weeds which take over our plantations we amateur gardeners use glyphosate, too. Glyphosate is the major component in weed killers such as Roundup.

Are we poisoning ourselves?

There are safer, alternative ways – albeit few – of discouraging weeds from killing crops, yet they are far less ‘easy’ to apply than glyphosate compounds, more labour  intensive and in most cases much more expensive and (so far) less effective. A rapid withdrawal of glyphosate would hit farmers hard.

intensive and in most cases much more expensive and (so far) less effective. A rapid withdrawal of glyphosate would hit farmers hard.

So why look for alternatives when glyphosate is so easy to mix and apply?

Numerous scientific reports mandated by different public and private bodies – who have their own interests – have been conflicting. They shed much doubt on the safety of glyphosate based compounds for human health. The molecule is considered by some as cancerogenic, responsible for non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma and endocrine imbalances in the population: the herbicide contaminates the water table and hence crops and food. Alarm bells concerning over-use of glyphosate have been ringing for years. According to the World Health Organization, the US, South America, and particularly Argentina have seen huge health effects due to bad usage.

France is leading the fight in Europe for a ban on glyphosate, but so far the EU has not reached the majority vote needed for such a ban (a minimum of 55% of Member states, and 65% of the European population). France’s lead has been backed by a petition boasting 156,000 signatures launched by Foodwatch, Générations Futures and the Ligue Contre le Cancer. NGOs claim that “69% of French people are against re-authorisation” of glyphosates.

The European Commission has just extended (on 30 June) the EU license to use glyphosate, but only for a further 18 months, instead of the statutory 15 years. It has meanwhile mandated the European Chemicals Agency/ECHA to continue scientific testing. The ECHA will report back end December 2017.

What is glyphosate?

Glyphosate is the most frequently used herbicide in the world. It is a broad spectrum herbicide, a chemical compound soluble in water and can be used mixed with other herbicides. It eliminates or significantly reduces hardy weeds such as ray-grass and brome grass which kill or inhibit the growth of crops. It is also used by farmers to kill above ground growth of weeds. First synthesized in 1950 by a Swiss chemist and later abandoned, glyphosate was rediscovered by a Monsanto chemist in 1970. Monsanto marketed it in 1974 under the name Roundup. Other trade names using glyphosate include Rodeo and Pondmaster. In the public eye it has been – and still is – erroneously associated with GMOs. However, whereas GMOs are no longer authorised in 19 EU countries (including France), glyphosates remain in use.

The Good, the Bad and the Ugly

The Good, the Bad and the Ugly

The plus side: Glyphosate has enabled a large increase in crop production throughout the world, thus ensuring a steady world-wide food supply. It is not labour-intensive, saving farmers much time and money. It is inexpensive, and has been under constant scientific surveillance – in the EU since 2012.

It is worth noting here that if the EU Commission is highly concerned about tightening safely regulations, each country is under no obligation to enforce EU measures on herbicides and pesticides: it is the responsibility of each Member state to decide whether to follow them or not. That said, the EU Commission has one of the strictest scientifically based assessments of herbicides and pesticides in the world. Public sector scientific experts from the European Union’s Agencies such as EFSA and ECHA and EU national authorities in all 28 member states carry out regular assessments of glyphosate use.

Envilys, a renowned French enterprise offering professional training and advice for agricultural and environmental practices, claimed in 2012 that without glyphosate – and returning to mechanical weeding and alternative selective herbicides – farmers can expect to pay an extra 100 Euros per hectare (2.47 acres); and will experience a 30-40% drop in yield. These figures are backed up by the Plateforme Glyphosate.

Despite the reported close scrutiny, glyphosate still has a very bad press. And with reason. Conflicting reports of possible links to disease and food saftey mentioned above have raised alarm.

Those platforms who lobby for glyphosate point out clearly that it is not toxic if used in the proper quantity and under recommended conditions, backing up their arguments with numerous scientific studies. Can we trust farmers to use the proper dosages? Can we be sure they are not contaminating crops and the water table? And then can we trust ourselves to use correct measures of glyphosate in our gardens and our public places?

How much are we all poisoning ourselves by being inattentive to dosages?

As stated in my article To Bee or not to Bee on neonicotinoids, we are all in the dock once again.

And, can we trust the scientific reports who say it is safe, given that some are mandated by the companies who manufacture the molecule and have a vested interest in keeping it on the market.

I have tried to clarify what experts are saying, since conflicting reports on glyphosate have caused much confusion.

Who says what?

EFSA – the European Food Safety Authority reports that glyphosate is unlikely to be cancerous. However, it should be noted that EFSA – so far – only evaluates the active product, and has not evaluated it when mixed with other molecules to enhance it (‘formulated’ glyphosate).

EFSA – the European Food Safety Authority reports that glyphosate is unlikely to be cancerous. However, it should be noted that EFSA – so far – only evaluates the active product, and has not evaluated it when mixed with other molecules to enhance it (‘formulated’ glyphosate).

In summer 2015 the European Commission asked EFSA to reconsider their verdict.

Since then, the International Agency for Research on Cancer/CIRC (a World Health Organization agency) reported that ‘formulated’ glyphosate is most probably cancerous. (see below).

The EFSA responded to CIRC’s report by advising individual countries to investigate the molecules being added. But it repeated again in November 2015 that it is unlikely the active product is carcinogenic, quoting thousands of scientific pages and publications. See full conclusions here.

More than ninety scientists last November wrote an open letter criticizing EFSA’s response . EFSA in return argued that their own study and that of CIRC’s cannot be compared because EFSA’s was an ‘exhaustive risk evaluation’, whereas CIRC’s was only a ‘first evaluation’.

NGOs have openly attacked EFSA and Monsanto for distorting scientific analyses.

CIRC International Agency for Research on Cancer/CIRC: As mentioned above, the CIRC is a specialized agency under the umbrella of the World Health Organization, whose studies – unlike EFSA’s – take into account “formulated” glyphosate. In March this year 2016, CIRC concluded that glyphosate probably is cancerous. It is their particular report which threw into disarray the European process of re-allowing it.

CIRC International Agency for Research on Cancer/CIRC: As mentioned above, the CIRC is a specialized agency under the umbrella of the World Health Organization, whose studies – unlike EFSA’s – take into account “formulated” glyphosate. In March this year 2016, CIRC concluded that glyphosate probably is cancerous. It is their particular report which threw into disarray the European process of re-allowing it.

Anses, the French Agency for Food, Environmental and Occupational Health & Safety, reported in June on risks linked to mixing chemical compounds such as glyphosate to phyto-pharmaceuticals. (Phyto-pharmaceutics are composed of natural components derived from plants, as opposed to chemically synthesized components.) On the basis of their findings, Anses withdrew 20 products for amateur use in France, including Roundup – although for some dubious commercial/politico reason, Roundup can still be found on some shop shelves when I go down town … Anses says there is no persuasive scientific proof that there are no risks for health, and calls for no less than 132 products to be taken off the market in France. Anses is currently continuing tests.

Anses, the French Agency for Food, Environmental and Occupational Health & Safety, reported in June on risks linked to mixing chemical compounds such as glyphosate to phyto-pharmaceuticals. (Phyto-pharmaceutics are composed of natural components derived from plants, as opposed to chemically synthesized components.) On the basis of their findings, Anses withdrew 20 products for amateur use in France, including Roundup – although for some dubious commercial/politico reason, Roundup can still be found on some shop shelves when I go down town … Anses says there is no persuasive scientific proof that there are no risks for health, and calls for no less than 132 products to be taken off the market in France. Anses is currently continuing tests.

Plateforme Glyphosate: This lobby group![]() s 7 firms, including Monsanto, who commercialize preparations with glyphosate at their base. The companies are based in 12 EU countries. Unsurprisingly they back the EFSA’s assessment saying it is unlikely cancerous, although they acknowledge that the future of glyphosate should be questioned. But they don’t envisage it being taken off the market.

s 7 firms, including Monsanto, who commercialize preparations with glyphosate at their base. The companies are based in 12 EU countries. Unsurprisingly they back the EFSA’s assessment saying it is unlikely cancerous, although they acknowledge that the future of glyphosate should be questioned. But they don’t envisage it being taken off the market.

![]() ECHA: the European Chemicals Agency has been mandated by the EU Commission to continue research; their report is due 31 December 2017, when the present EU license for use runs out. Depending on their report, glyphosate will either have a renewed license, or will be banned.

ECHA: the European Chemicals Agency has been mandated by the EU Commission to continue research; their report is due 31 December 2017, when the present EU license for use runs out. Depending on their report, glyphosate will either have a renewed license, or will be banned.

![]() Générations Futures, the Paris-based NGO calls for a straight ban on glyphosate whether associated with other products or not, quoting CIRC’s findings of them being ‘probably’ cancerogenic.

Générations Futures, the Paris-based NGO calls for a straight ban on glyphosate whether associated with other products or not, quoting CIRC’s findings of them being ‘probably’ cancerogenic.

Clear? While we await even further analysis and decisive scientific agreement end 2017 as to its toxicity, what are the alternatives?

Alternatives

Weed management does not necessarily mean only using herbicides. Herbicides can be used responsibly as part of an integrated way of crop management. Some weeds can become resistant to herbicides – most likely as a result of over-use. (It is worth noting here that in the US, some crops such as corn, soya beans and cotton have been genetically modified to be herbicide tolerant…)

Since glyphosate may be banned in the next 18 months after ECHA’s report, it is urgent to find alternative methods. Here is what is being done in France. (See end of this article for UK and USA websites on pesticides).

- Less intensive cultivation of the land.

- A combination of mechanical weeding (ploughing) with different types of machinery, alongside chemical weeding. Ray grass and black-grass (also known as slender meadow foxtail, twitch grass, black twitch) are particularly difficult to eradicate: labour-intensive turning of the soil is combined with safe measures of herbicide.

Ray grass – invasive crop-killer, difficult to eradicate - According to surveys, many farmers in France no longer automatically use glyphosate. One farmer interviewed uses just 0.5 – 1 litre per hectare (2.4 acres) mixed with 60-80 litres of water. By using so little he reduces his costs and the risk of contaminating the crops and the water table. He treats his crops morning and evening when the winds are low, and uses rain water to dilute the substance. However, some farmers have been found mixing as much as 3-5 litres glyphosate per hectare.

- The French Chamber of Agriculture tested different methods of weeding against ray-grass and recommends waiting until beginning November to sow, and says combining mechanical labour/ploughing with chemical treatment can greatly reduce ray-grass – from 300 to 1 per square metre.

- Spring planting: this significantly reduces weed cycles.

- Investment in agricultural machines. Use a tiller and a rotating harrow in autumn to prepare the earth for spring cultures, followed by more mechanical weeding in spring. One farmer interviewed in the French agricultural magazine La France Agricole* invested with fellow farmers in a sophisticated harrow, a hoe with 12 rows of teeth for beet, and one with 6 rows of teeth for maize. He plants mid-April. For beet, after the 3rd leaf, he twice sprays low-dosage chemicals so as not to ruin young shoots, then does mechanical weeding – just once – with a harrow and hoe. To eliminate the tenacious ray-grass he could space his plantations out more to allow for more radical ploughing, but this would mean less crop, so instead he sprays chemicals. New, more sophisticated, ploughing machines exists – at a cost – which would avoid this problem.

Tiller

Disk harrow - Ploughing/weeding the soil in humid conditions: the job is easier and makes a big difference to crop health and productivity.

- Bio-related techniques: trick the weeds with rotation. Varying crops, using more and more different ones, is an effective way to eradicate tenacious weeds. The key lies in alternating crops in winter and spring. Specialists agree that one of the best ways is to change species successively, planting alfafa or a mixture of species for 2-3 years. According to the Chamber of Agriculture in the Drome area, “perennials,

Rotating crops tricks weeds bindweed and wheatgrass … disappear naturally when you change rotations.” A specialist from the French National Institute for agro-economic research/Inra reports – from the Dijon plains – that adding soja or spring barley in the colza-corn-barley rotation eradicates wheatgrass. Thistle and rumex (docks, sorrels) are, however, resistant to rotation methods, but you can make them disappear by planting alfafa and persistenly reaping them. Adding another culture to a succession of three different species can cut by half the amount of weeds – from 142 – 65 plants per square metre.**

- Use appropriate machinery: to extract rhizomes, use a machine with teeth to bring them to the surface where, once there, they will dry up. Using a machine with disk shaped heads encourages wheatgrass.

- Permanent cover. This method avoids labour-intensive mechanical weeding. For cover, use oats and mustard which reduces weeds, coupled with rotation. This is a method used by the French Association pour la promotion d’une agriculture durable.

France’s Plan Ecophyto 2018 was to reduce herbicides and pesticides by 50% between 2008 – 2018, but the deadline has been extended to 2025. Within the framework of Plan Ecophyto2, the French water agencies offer grants to farmers who change their methods to more sustainable farming, thus protecting the water table.

Help the Farmers

Farmers throughout the world face huge difficulties adapting to new rules, regulations and new high-tech farming technologies; they need training in both management and technology – IT, new machines, how to manipulate new products, and they also need psychological help, and money. It can be a nightmare for them.

France struggles – through different agricultural agencies – to help farmers on the brink of suicide, to help bereaved families who’ve lost a member who has committed suicide in face of such drastic, fast-moving changes. OECD agriculture ministers last April called for more government aid at national levels for farmers changing over to sustainable farming methods. See Glyphosate and alternative farming for French official bodies offering aid to farmers.

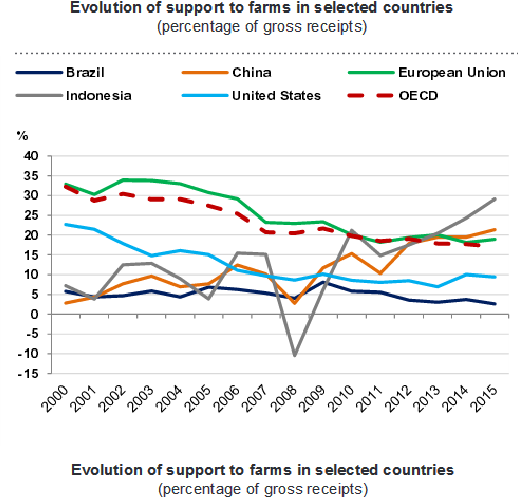

An OECD report of April 2016 shows big differences in the level of aid offered to farmers per country. Korea, Iceland, Japan, Norway and Switzerland are the most generous in their subsidies to farmers, followed by Indonesia, then China. The Russian Federation, Turkey and the European Union are considered the norm. But the US, Canada, Brazil, South Africa, Chile, Columbia, Israel, Kazakhstan, Mexico, New Zealand, Ukraine and Vietnam offer much less to their farmers.

___________________________________________________

* La France Agricole, printed version, 13 May 2016

** La France Agricole, printed version, 17 June 2016.

The latest EU regulatory process on glyphsates can be found here.

Official UK statistics on the use of chemicals can be found here.

The UK government’s Health and Safety Executive webpage on chemicals can be found here.

The US Environment and Protection Agency’s website on Food and Pesticides can be found here.

____________________________________________________________________

Protection of the land in France is becoming more codified. New “zones” have been drawn up where certain phyto products – products made up of different plant-based components – are forbidden. They are:

- No-treatment zones: “ZNT” – zone non traitée – to protect surface water, plants and arthropods from contamination.

- Permanently vegetated areas: “DVP” – dispositifs végétalises permanents – to protect surface waters from being contaminated by streams. These areas have to have permanent herbaceous cover preferably with a protective hedge around them. Nearly half of herbicides in France require a DVP licence.

- Uncultivated adjacent zones, “ ZNCA” – Zones non cultivée adjacente, to protect arthropods and plants from contamination.