If you went down to our woods eight years ago you’d have heard and seen ten beehives  amongst the birches. Coming in closer, thick clouds of bees would have swarmed around you like an army attacking. Our neighbour Madame Lenoir had bees too, in her back garden. Her son drove up with them in the back of his car from Paris and they escaped on the way, out of their hives. So determined he was to get them to his mother’s house that he just wound up his windows, put on his hood, grit his teeth and drove on.

amongst the birches. Coming in closer, thick clouds of bees would have swarmed around you like an army attacking. Our neighbour Madame Lenoir had bees too, in her back garden. Her son drove up with them in the back of his car from Paris and they escaped on the way, out of their hives. So determined he was to get them to his mother’s house that he just wound up his windows, put on his hood, grit his teeth and drove on.

Two years later Madame LenoIr had no more bees. And there were no more beehives in the woods.

Three-quarters of the world’s agricultural food crops require pollination, most of which is done by bees. So bees are a very serious business. Our world food supplies – and thus our security – depends on them.

Yet bees are on the decline. Who, or what, has been killing them? That is the question.

Fingers have been pointed at neonicotinoids, those nasty sounding insecticide chemicals we spray on our crops. No-one denies that the misuse of neonicotinoids causes poison, but a broader picture has to be drawn. The international media tend to focus almost exclusively on neonicotinoids, blaming the chemical giants for having marketed them. Yet bee facts are infinitely more complex.

Killer pests and diseases are equally guilty scientists say, as well as climate change and colony mismanagement.

First let’s look at statistics.

Statistics

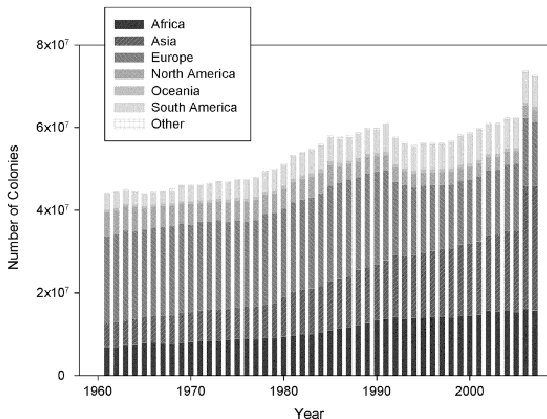

It’s important to note that according to historical statistics published in the Journal of Invertebrate Pathology/Elsevier, honey bee populations overall throughout the world have in fact increased over the last 50 years. But the devil is in the detail, because the increase hasn’t been universal.

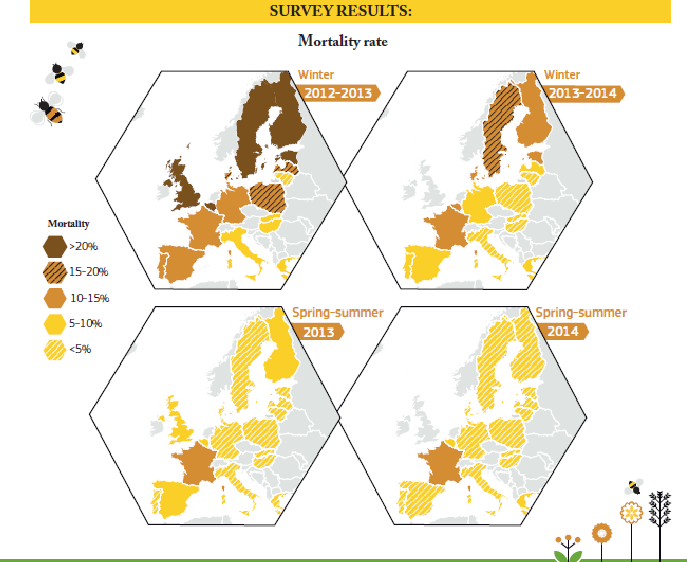

It is notably in Europe and North America where steep declines in managed populations have been reported, with some individual countries in those areas seeing increases, others decreases. Are those countries where numbers are falling the ones misusing neonicotinoids? Are they mismanaging their colonies? Has the climate there been particularly fierce? What pests have invaded, and where?

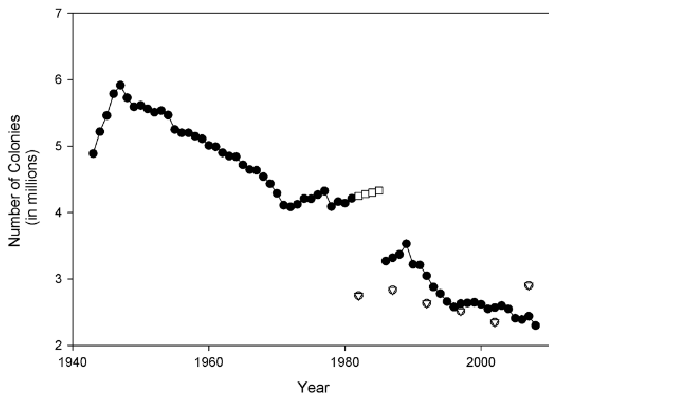

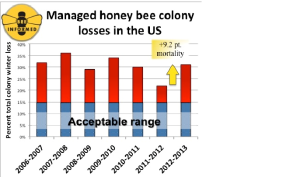

It has been difficult to find comparative historical figures on bee populations; the independent OPERA Research Center is gathering recent European figures but otherwise there appears to be no Europe-wide centralised historical data, unlike in the United States, where US data has been collected by the National Agricultural Statistics Service. The Journal of Invertebrate Pathology/Elsevier reports that honey-producing managed colonies in the US dropped 61% from their high of 5.9 million in 1947 to the low of 2.3million reported in 2008. – (see above chart). As for Europe, Food and Agriculture Organization statistics quoted by the Journal of Invertebrate Pathology show that colony numbers fell from over 21 million in 1970 to about 15.5 million in 2007, a much steeper decline observed after 1990, which would coincide with the introduction of… neonicotinoids.

The UNAF, the French National Union of Bee-keeping, tells us that 300 000 hives die off each year in France alone. Since 2006, the US and Europe has seen unusual decreases and disappearances, representing an average total of 30.5% from 2006-2012. In the winter of 2013, losses were 42% higher than the previous year. Several national colony monitoring programs are now set up, with specialists pointing out one of the most comprehensive ones: the German Honey Bee Monitoring Program* which although laborious and expensive to run has generated reliable data enabling relationships to be determined between risk factors and colony death.

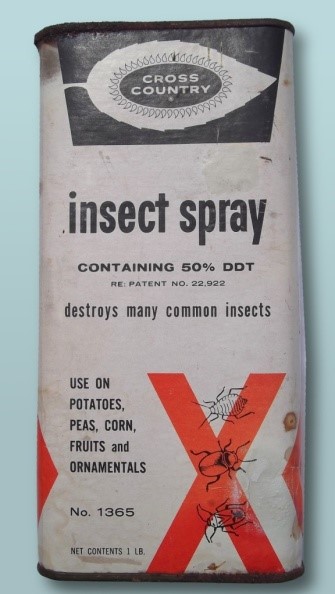

History: DDT and Neonicotinoids:

Prior to neonicotinoids there was DDT (dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane). Synthesized in 1874, DDT was first used for the control of malaria before being recognized in 1939 as a powerful insecticide. Despite health warnings from doubting scientists and environmentalists, the 1940s and 50s saw DDT being lavishly sprayed on our crops to destroy ravaging insects. Rachel Carlson’s book “The Silent Spring”, published in 1962, helped raise public awareness, warning of the devastating effect on health and the environment. Anti-DDT lobbies gained the forefront, but it took another forty years before the international environment treaty, signed in 2001, banned its use. The treaty** came into effect only in 2004.

Meanwhile in the 1980s, with the object of finding a safer replacement for DDT, Shell researched and refined synthesized chemicals which Bayer later patented: the 1990s saw the birth of neonicotinoids.

Neonicotinoids: let’s first get the name straight: neonicotinoids is a family of five neuro active insecticides with a surname easy to memorize because it includes the word nicotin – this family is chemically similar to nicotine. The seven members of the Neonicotinoids family are thiamethoxame; clothianidine; imidaclopride; acetamipride; thiaclopride, dinotefuran and nitenpyram. Go memorize those… But we all use them in the garden, as well as on our crops.

History repeats itself: as with DDT, similar, well documented concerns have been raised about the safety of neonicotinoids, too. But it has taken thirty years for the European Commission to implement a two-year ban on the use of three neonicotinoids while  awaiting further research. Meanwhile the French Parliamentary Assembly this year voted in an amendment prohibiting the use of neonicotinoids because of their probable devastating effect on bees: but it will only be legally enforced in September 2018. Why wait?

awaiting further research. Meanwhile the French Parliamentary Assembly this year voted in an amendment prohibiting the use of neonicotinoids because of their probable devastating effect on bees: but it will only be legally enforced in September 2018. Why wait?

Because scientific researchers say that tests to date are inconclusive, and the French are holding back on the ban not only to give agriculturalists time to find alternatives – to be proposed by Anses (French national agency for food, environment and workplace security) – but to wait for more up to date scientific research being done by the The European Food Safety Authority (Efsa) reporting to the EU, whose report is promised for 2017.

The truth is that results of laboratory tests on bees are not representative of the reality out in the field, scientists say. More study in the field needs to be done. Bees work in swarms whereas in laboratories, tests are on single bees – or very few of them. An OECD report says bee stress is a factor to be taken into consideration; “bees are affected by stress if they are tested for more than 48 hours”.

The truth is that results of laboratory tests on bees are not representative of the reality out in the field, scientists say. More study in the field needs to be done. Bees work in swarms whereas in laboratories, tests are on single bees – or very few of them. An OECD report says bee stress is a factor to be taken into consideration; “bees are affected by stress if they are tested for more than 48 hours”.

Pests and diseases

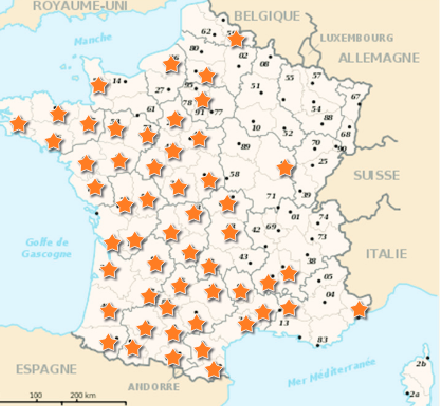

Deformed Wing Virus (DWV) on adult bee. Source: Asian Hornet findings in France, 2013. Source: OPERA Research Center; Bee Health in Europe

The independent think tank OPERA Research Center points the finger at pests and diseases. For example, the Varroa destructor is particular devastating for honey bees; it is hosted by the Asian Honey Bee who also disseminates and activates a number of viruses such as deformed wing virus, considered to be the most

widespread bee virus in Europe, and one of the key players in colony losses. Nosema spp is another culprit, first reported 100 years ago, but in Europe only in 2005. There’s the Asian Hornet – vespa velutina – and a host of other pests and diseases. All these ‘enemies’ need to be weighed up against other interacting factors – as mentioned before: climate, misuse of pesticides, bad bee colony management. And, very importantly, human behaviour.

Human Error and the Anthropocene Age

Scientists argue that we have entered a new era, where human activities impact on the global ecosystem, causing the extinction of plants and animals by polluting and altering the earth’s atmosphere – indeed, our natural landscape is receding. They call it the Anthropocene Age: we should look to our own human behaviour, too.

- Bees are being used by man as carriers of microbial pesticides, i.e. to spread some pesticides, and are therefore under direct exposure as well as indirect exposure. See this OECD report.

- The Asian hornet, a predator of honey bees, raiding colonies and attacking on the wing, were accidentally introduced into France by man via a container ship, caught in a box of Chinese pottery being delivered to Europe and spreading at 100 kms per year in 2013 in France alone.

- Trade: despite restrictions, importing bees to pollinate crops comes with risks: diseased bees can be imported, unwittingly or not. Bee smuggling, – the illegal importation of queens or bees – has been considered a major vehicle for the spread of bee diseases and parasites.

- Weather and climate change. Extended periods of cold, rainy, and hot weather effect bee health.

- Economics and politics: it has been suggested that the collapse of the Berlin Wall caused the reported rapid decline of bees in Europe in the 1990s. Before the Wall came down in 1989, honey served as a second currency in the Soviet Union. After the fall of the Wall, there was no longer the need to keep colonies. Eastern Germany alone saw a 75% drop in one year in its honey production. This obviously effects and distorts overall statistics.

Honey Bee Colony losses in the US 2006-2013. Source: www.beeinformed.org - US beekeepers have used the parasite Varroa destructor – a mite highly resistant to insecticides – to control other mites from inside the beehives. A joint EPA-USDA study says that this alone has been the biggest cause of bee deaths.

- The misuse of products: OPERA states “it is important to note that the most frequent causes of adverse effects of pesticides to bees are the misuse of products and/or ignorance of product label statements by farmers, combined with a poor communication with beekeepers, or disregard by the latter for good beekeeping practices.”

Collecting figures, research, and interpreting the reasons for bees dying is a difficult task. For example, according to Anses, the French national food security agency, we need to remember that it is normal that bees die in their hives. Every winter 5- 19 per cent of colonies die anyway and, during the rearing seasons (February/March, and September/October), many die each day.

Anses lists all possible reasons for death here, and recommends better use of neonicotinoids here. France meanwhile, the OECD says, has conducted one of the most extensive monitoring programmes to survey the bee safety of thiamethoxam seed treatment in maize: the results, according to the French Ministry of Agriculture, were that they found no product-related effect on colonies, even after several years of exposure.

Suspect products under moratorium are awaiting further analysis. The European Food Safety Authority (Efsa) reporting to the EU Commission will finish its risk assessment of pesticides for bees in January 2017 upon which informed policies can be made.

So there are many culprits, even if we haven’t yet come to a precise verdict. But there is no smoke without fire, and neonicotinoids cannot escape without utter scrutiny. And, in this new Anthropocene Age, should we not look more closely at our own behaviour? We’re often ready to blame others: we blame the chemical giants with their financial greed for thrusting dangerous solutions on us to solve agricultural challenges; the giants in turn blame us for misuse: read the instructions, silly, if you use the right dosage… By human nature we can be sloppy or, worse still, greedy for a quick gain at the expense of all of us, including bees, who enable our crops to grow and thus ensure our food safety. So everyone and everybody is in the dock.

See also France votes in ban on neonicotinoid insecticides

_______________________________________________________________

* German Honey Bee Monitoring Program: http://www.ag-bienenforschung.de

**Stockholm Convention on Persistent Organic Pollutants

EU actions on bees since 2012 can be found here.

US survey reports on bee losses since 2008 are recorded here.

The European Commission in November 2015 gave recommendations for the proper use of neonicotinoids.

If you are in France, when you next go to spray your garden to drive off those nasties, check in on this usage chart published in January 2016 by the very thorough French national agency for the security of food, health, environment and labour.