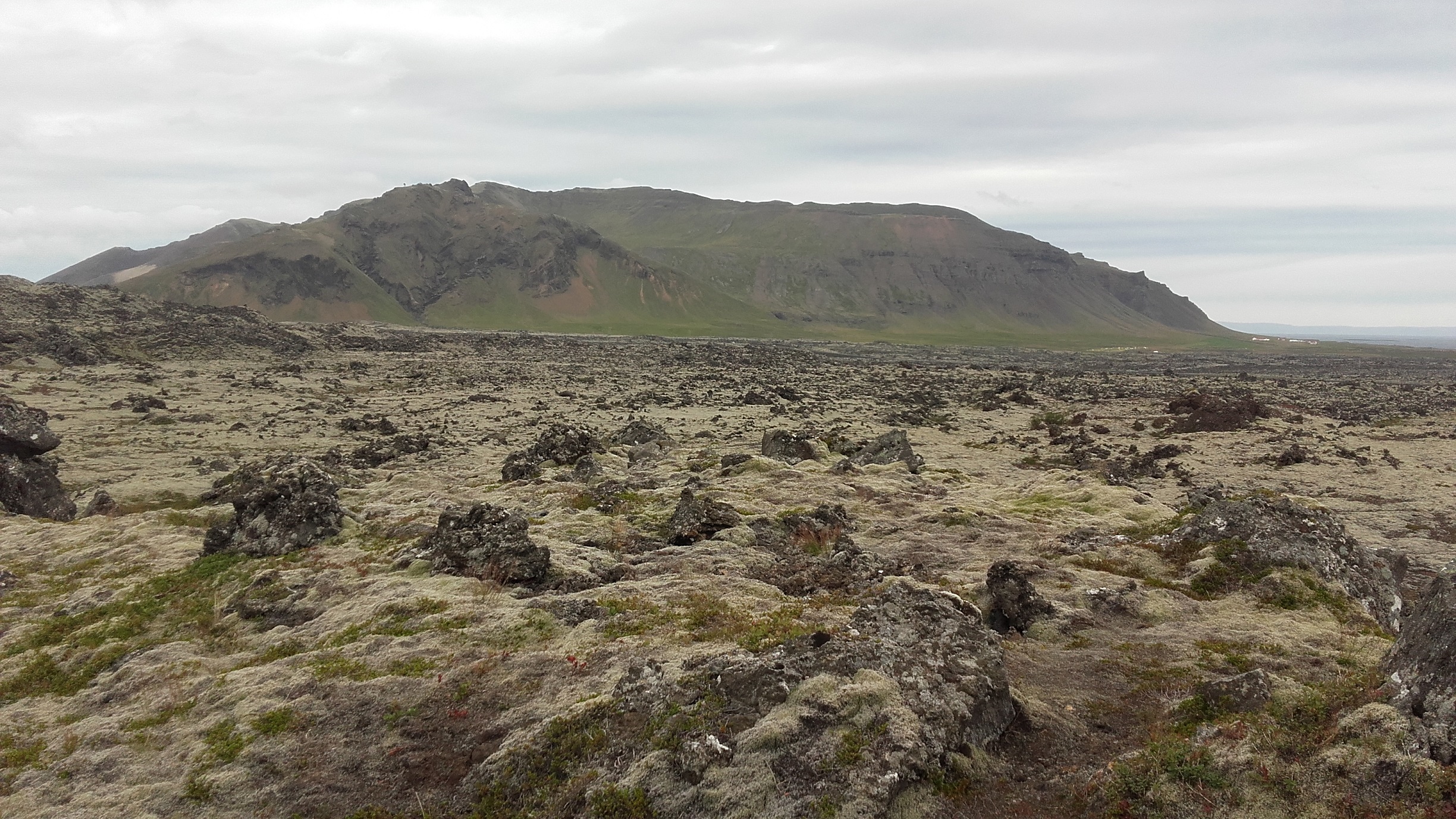

In Iceland, vast swathes of silvery moss spread over endless stretches of land which has been ripped up by volcanic shifts and eruptions. Unlike the chaotic, jagged basalt boulders and the ravines beneath, the moss lies like a smooth blanket, or rather a damp poultice, over the vestiges of violence and smothering them.

The contrast of soft and hard, violence and calm could not be more striking. Rocks and moss here exist in a kind of symbiosis, the basalt bumps, protrusions and some gaping caverns offer themselves up as the moss’ host as if in reparation for its violent wrong-doing, the moss covering it all up.

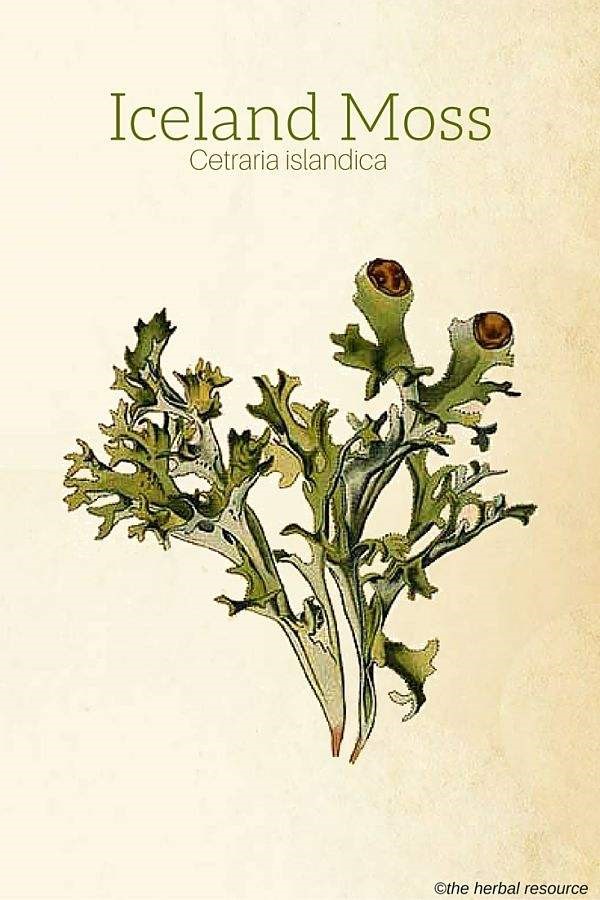

Despite its name, Icelandic moss is strictly a lichen. It belongs to the family Parmeliaceae; its botanical name is cetraria islandica. Unlike moss, it is not a plant. It is a composite organism made up of fungi and algae which work together in symbiosis: the fungi part takes care of water and minerals, the algae form the biological material through photosynthesis. It contains lichen acids and a high proportion (around 70%) of carbohydrates in the form of bonded sugar molecules (polysaccharides).

Icelandic moss has provided, and still does, a rich source of food in Iceland. Unlike the deadly fires and eruptions which decimated entire communities over the centuries, the ‘moss’ which came later to smother the rocks provided a rich source of sustenance for the inhabitants going through hard times. Historically, it was widely used in breads, porridges, and soups – in its powder form it was used traditionally in northern Europe as a thickener in soups. It is still eaten in Iceland, Norway, Canada… and thanks to the health revolution it is being included once again in the food industry.

It also has strong medicinal properties. It is an anti-oxidant, a powerful antibiotic (usnic acid and other lichen acids combat bacteria and viruses). It is rich in mucilages (e.g. proteins) and has been used in Iceland for respiratory ailments such as bronchitis, asthma and TB; also for curing digestive problems such as gastritis, food poisoning, constipation – and more recently irritable bowel syndrome. It serves as a poultice on eczema and dry skin wounds. It is considered an effective natural treatment for conditions such as malnourishment, debility, and anorexia.

In fact the more you learn about it, the more you understand why we are told not to walk on it, not to disturb its natural growth: Icelandic moss is a precious commodity.

Its medicinal properties were most probably first known to the natives of Iceland; it is used in traditional Chinese medicine, and was recorded by the Danish scientist and physician (and poet) Borrichius, who tells us that Danish apothecaries were acquainted with the medicinal applications of Iceland moss in 1673.

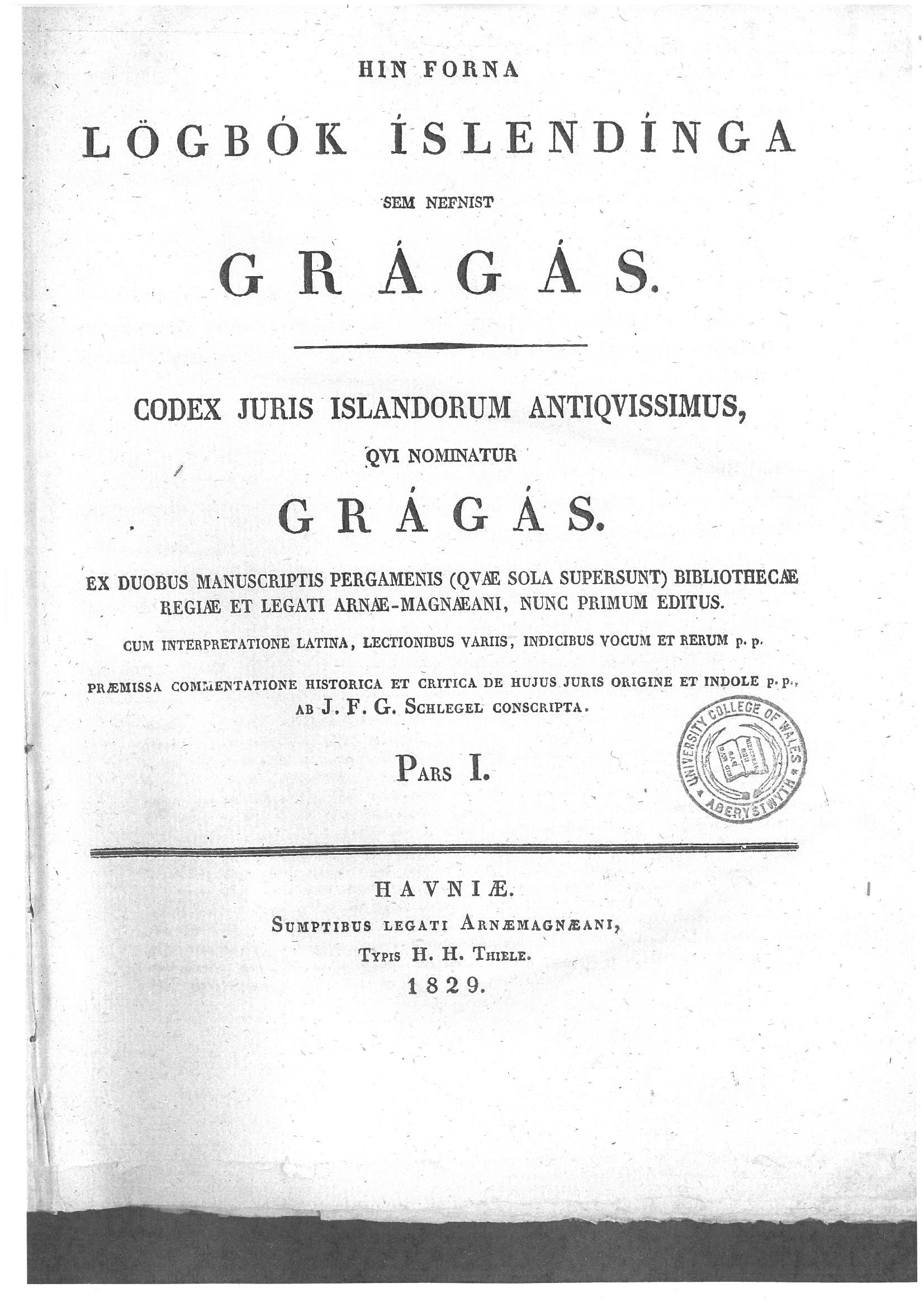

Icelandic ‘moss’ has been used in Iceland since settlement times in the 9th century. The Vikings ate it – it is mentioned in the Grágás – the Grey Goose Laws of early Iceland.

The Icelandic Sagas tell of lichen-picking expeditions where women and children went up on horseback into the mountains to pick it (under the supervision of an adult man). They slept in tents and packed the lichen in skin bags. It was a life-saver in hard times. Two barrels of moss was considered the nutritional equivalent of one barrel of flour. Since grain growing in Iceland never took off due to the unsuitable climate and terrain, moss was their staple. The more moss you had on your land, the more valuable your land. It was considered a food rich in minerals – iron, calcium and fiber.

After washing it clean, and drying, it was eaten as whole, or chopped up, boiled in milk to make a kind of porridge, and in hard times was used to eke out bread, liver sausage and other offal dishes.

During the Haze Famine, caused by the 1783 Laki eruptions (known as the Skaftár Fires in Iceland) which spread a haze of acid rain over not only Iceland but a large part of the northern hemisphere, the Icelandic people saw their main food sources destroyed, including their staple lichen. The lichen took six 6 years to grow back.

After the dire effects of the Haze, which brought on famine in Iceland and most of the northern hemisphere, Icelandic moss was promoted throughout the 19th century as famine food in not only in Iceland but also in Norway, Finland, Sweden, Germany, Russia, France… Botanists and economists, learning from the traditional use in Iceland, published recipes on lichen bread, lichen gruel and lichen pancakes.

And, as mentioned above, thanks to the health revolution, Icelandic moss is back in a big way in modern Iceland: you can buy it in tea form mixed with other indigenous plants such as angelica and thyme. It is easily found in numerous alternative medicines.

As for food, in Reykjavik you can buy bread with ingredients which include Iceland moss ground to flour.

In fact Iceland moss is no longer a staple: it is a delicacy – seen as a novelty by some who are visiting – and is included in culinary dishes. Here are a couple of recipes, and you can check in on Icelandic Chef Völundur Snær Völundarson’s prizewinning recipe book Delicious Iceland.

Lichen Milk Soup:”Fjallagrasamjolk“

large handful of Icelandic moss (can be bought at this Viking website)

large handful of Icelandic moss (can be bought at this Viking website)

1 litre (4 cups) milk

1 tbsp sugar or brown sugar

salt

Wash and dry moss. Pour milk into a saucepan, heat to the boiling point. Add moss and sugar, simmer for 10 minutes. Add salt to taste and serve.

Iceland Moss Bread: “Fjallagrasabrauð”

taken from website (Icelandic only): http://www.allskonar.is/uppskrift/fjallagrasabraud.

10 g Icelandic moss

water

375 g whole wheat

75 g ground barley flour

100 g oatmeal

35 g sunflower seeds

2 tbsp sugar

1 tablespoon baking powder

1 teaspoon baking soda

1 teaspoon salt

5 dl milk (or other liquid )

Preparation: 20 minutes. Baking time: 60 minutes.

Soak the moss in a bowl of cold water to clean. Mix dry ingredients in a large bowl: whole wheat flour , barley flour , oat, rice , sunflower seeds , sugar , baking powder , baking soda and salt . Stir well. Prepare 2 small bread pans. Heat oven (no fan) to 190 °. Add the moss, milk and water and mix well. You can use soy milk , almond milk , oat milk, buttermilk , yogurt or just pure water if you do not use milk .Divide the dough into shapes and bake near the bottom of the oven for about one hour until the pin comes out clean when you slip it into the dough. Good with butter and cheese.

Enjoy!