For farmers up here in Normandy, Brussels – whose Commission regulates farming practices throughout Europe – seems very far away. And so does Paris. They say that neither the European Commission nor the French government have a realistic notion of what the average farmer has to cope with in order to provide the food we depend on; regulations are very cumbersome.

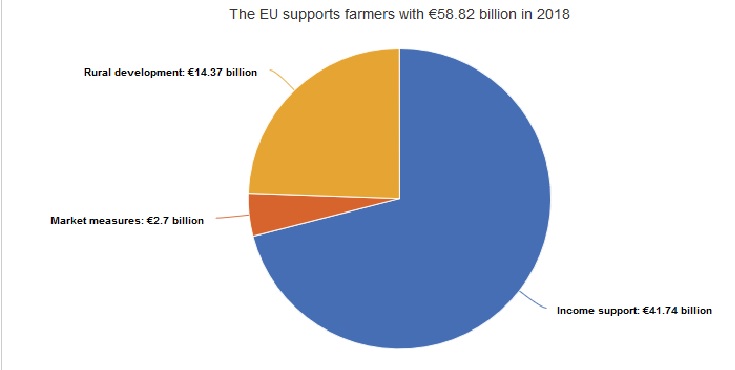

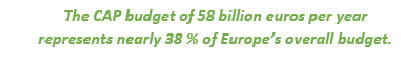

Yet most of the money paid to farmers comes from the European Union budget, paid for by contributions from member states. A share of that money from that the EU budget is put into Europe’s Common Agricultural Policy (CAP). French farmers are the largest beneficiaries of the Common Agricultural Policy in Europe, receiving 9.1 billion euros per year for the period 2014-2020.

Last week on 18 March, agricultural ministers came together in Brussels to study proposals for a new, modernised and simplified Common Agricultural Policy which will cover the period 2021-2027. Discussions for this new phase of CAP began in 2016 and legislative proposals were presented in June 2018.

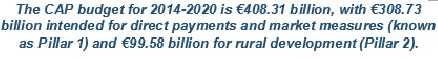

Negotiations are taking place in the context of an overall EU reduced budget, due not only to Brexit but to other new issues such as migration and security. The CAP budget will drop almost 10% cent, from 37.6 % of the overall EU budget to 28.5 % for this next phase.

Complaints from French farmers about their working conditions and about heavy bureaucracy ‘dictated’ from Brussels are real and have abounded over the years. They have to spend a lot of time keeping up with EU regulations in order to receive the financing they need.

True, it runs in French blood to complain; sentences during any discussion over here often begin with ‘Non mais’ (No, but…). But in this matter there is some justification, given the complexities of rules and regulations dictated by CAP.

Origins

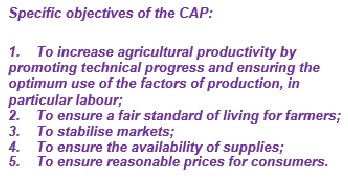

Let’s take a quick look back at the history of the Common Agricultural Policy. The CAP was launched by EU member states in 1962 to ensure wholesome food for Europe after the devastation of World War 2. It offers financing and specialist advice for European farmers who in turn adhere to environmental and climate-friendly regulations. It also provides financing for regional development.

Over the years the CAP has undergone five major reforms, the latest in 2013 and is now entering its next phase for the period 2021-2027.

The European Union has become one of the world’s leading producers and net exporters of agri-food products. It aims to improve food production, rural community development and environmentally sustainable farming.**

What is being proposed for the new CAP 2021-2027?

Decentralisation: more responsibility for Governments

- Responsibility will be handed over to national governments. This means that the onus is on each country to choose how and where to invest the CAP funding. Each government will monitor and apply regulations themselves on a national level, and will decide, for example, which farmers should receive financial aid. The choices made will be based on the CAP agreed goals which are, amongst others, to 1) respect biodiversity, 2) respect climate change and in their words to 3) “achieve a sustainable, modern and competitive agricultural sector”, and “ensure fairer and better targeted support of farmers’ income.”

Financial aid must go to ‘real farmers’, with preferential treatment for ‘family farms.’ And it seems that each country is left to define its own notion of what a ‘real farmer’ is, of what a ‘family farm’ is, and as it stands so far there are other notions for which countries are left to interpret as they see fit, such as ‘young farmers’ and ‘permanent pastures’.

The new CAP would no longer be linked to legal texts, proposals say, but to analysis and overall approval. That is, the EC will no longer apply the EU law already validated by national legal authorities, but will judge the merits of political policies with no legal basis. The Commission has however promised guarantees on how the revised CAP is to be implemented in each country, such as giving approvals and conducting annual check-ups.

These proposals, which amount to devolution, are not enough to allay the fears of a nation with a long history of protectionism and mistrust of politicians.

Reactions

What’s left in common? What happened to the ‘C’?

The French governmental has welcomed the flexible and strategic approach, but voices concerns that the ‘C’ – the Common, in the Common Agricultural Policy may wear away. It asks for some common strategies to be maintained.

As for the French farmers themselves, despite their criticism of the European Commission, they fear re-nationalisation because they have a hard time trusting their own government with its renowned heavy bureaucracy and lobbies, let alone the EC.

The French farmers’ union Coordination Rurale warns of the risks of unfair competition where farmers could be tempted to disregard or at least compromise farming standards. The union demands more market regulatory instruments; for example, it blames the present crises in milk, pig and sugar sectors on deregulation ‘dictated’ by the World Trade Organisation. It asks for the present budget to be maintained and adapted to inflation, reminding us along with other Associations that agricultural and forest land represents 2/3rds of the EUs land.

The agricultural union FNSEA is likewise worried about farming standards dropping in the light of unfair competition, and fears that the minimum requirements for EU direct aid to farmers will be abandoned. It is also up in arms about opening the doors to Mercosur – the South American equivalent of the EU – which trades in products which do not have the same production standards as Europe.

Another farmers’ union, La Confederation Paysanne also deplores the dismantling of EU regulation, saying farmers will now have to face the agribusiness multinationals and food retail networks alone, a very daunting prospect for them.

Both Spain and Greece have raised similar concerns, with Greece unconvinced by the Commission’s subtle distinction between ‘subsidiarity’ and ‘re-nationalisation’. Germany, while saying the proposals are a good base to work from, is not convinced by the simplification proposal.

The present and outgoing Agriculture Commissioner Phil Hogan recognises that divergences still exist in the CAP proposals, that control methods need clarifying and that these elements and others need to be harmonised during the next EU Council meetings. These will pick up again after the European elections in May. The date for a political Agreement is set for October 2019. However, given the unresolved issues, and a new Presidency with a new configuration after the elections it looks as if farmers will have to wait until 2020 for a better idea of what the future holds for them.

*See the Commission’s UK country report here ; and the French country report here. All EEC country reports can be found here.