We were sitting on the steps of an orthodox church, its gold-tipped dome shimmering like a glorious crown in the sun. It stood on a bluff above the sandy clamming beaches, overlooking Cook Inlet and from our vantage point we could see in the distance the snow-capped range of Redoubt volcano on the other side of the inlet. We were in Ninilchik, Alaska, and we weren’t alone.

There was Cyril.

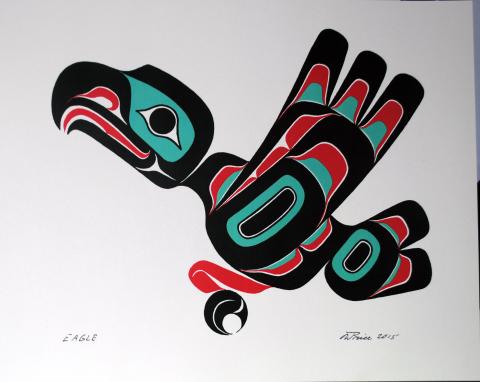

“Ah, that’s my father up there, watching out for me,” he said, waving his hand up towards an eagle which was circling round the dome above us. “That’s his spirit hovering.” He then delved his large fleshy index finger into the jamjar he had on his knees and pulled out a lump of King Salmon soaked in oil. The rich smell of fish mixed with the smell of iodine, kelp and salt from the sea below came wafting over to us on the other side of the step.

Cyril was a still-to-be-ordained orthodox priest standing in at this Church of the Transfiguration until the new priest arrived.

We’d first come across Cyril earlier that morning when we’d wandered inside the church. He was near the lectern, hunched up in a chair over a laptop and when he saw us he quickly stood up, his black cassock falling down covering his jeans and Nikes. He smiled kindly through his long, dark beard and gave us a warm welcome.

We knew his name was Cyril because a note was pinned on the door for visitors saying ‘Cyril’ could be contacted at such and such a number if anyone wanted a tour.

We hit it off well with Cyril. He gave us a bit of history while we stood all three of us in the vestibule of the charming little church, history concerning the Russian Orthodox Church in Alaska which he laced with titbits of his own personal opinion.

The Orthodox Church of America was set up by eight Russian Orthodox monks in 1794 at Kodiak Island when Alaska was part of Russia. The first American – as opposed to Russian – Bishop was appointed in 1799. In 1808 the monks moved down to Sitka and built a cathedral which they named St. Michael’s. St Michael’s became the seat of the Bishop of Kamchatka, the Kurile and Aleutian Islands and Alaska, representing an area covering over 2,000 miles. This was the “Golden Age” of the Orthodox Church in Alaska which ended when the United States purchased Alaska in 1867.

We walked out of the church with Cyril and sat on the steps and this was when he pulled out of some pocket in his cassock a jamjar of King Salmon floating in oil. While he sat talking with my husband my mind wandered down to the village beneath by the clamming beach. Earlier that morning we’d visited a small shop down there, an intriguingly untidy if not cosy little shop run by a friendly young woman. We’d browsed over the odds and ends of trinkets on sale: Russian dolls, Native American beads and basketry, silver Russian orthodox crosses, books on old dying cultures and I wandered too far into the  nooks and crannies and came face to face with a hot samovar and a table covered in a white frilly tablecloth. “No, that’s private, sorry…” the lady came up, coaxing me away. She told us she lived here with her Russian elderly mother. Indeed shop and home merged together in a weird mixture of cultures and time warps. It was like an old curiosity shop where the objects on sale represented an attempt to keep them alive against the odds.

nooks and crannies and came face to face with a hot samovar and a table covered in a white frilly tablecloth. “No, that’s private, sorry…” the lady came up, coaxing me away. She told us she lived here with her Russian elderly mother. Indeed shop and home merged together in a weird mixture of cultures and time warps. It was like an old curiosity shop where the objects on sale represented an attempt to keep them alive against the odds.

I homed back into the animated conversation Cyril and my husband were having.

“Difficult to take a vow of poverty when your salary is only 200 dollars a month,” Cyril was waving a piece of his oily King Salmon and the oil was dripping down his hand to his wrist. “But we were sent to be tried, weren’t we? I’m not fully ordained, you know. And won’t be able to be…” He sthesitated for a moment, then “I won’t be able to be ordained if, if I can’t find a wife, you see. You have to have a wife if you want to be ordained. I did have one once. But then we divorced. Well, I suppose some would say that I’m lucky the Church accepted me here, being alone and what. And divorced. But you know, it is lonely.”

We were’nt quite sure where to go with this information; my husband steered the conversation elsewhere. “Are you originally from Ninilchik?” It was a question waiting to be asked because Cyril’s face was particularly unusual and very arresting: it was wide-set, and his eyes were almost black, matching his long black and very shiny hair.

“I’m from the southeast”, he said. “I’m Tlingit.”

It explained his striking physique. Here was a tall, dark Tlingit Native American turned Russian Orthodox would-be monk, something which for a European outsider seems quite exotic. “I’ll be leaving here soon, in September,” he went on. “Off to the seminary on Kodiak, to do my training and get ordained. Three years, starting in September.”

Did I catch a quick grimace? Three years… Cyril didn’t look young. Perhaps in his early forties. Cyril was in a hurry. Then he said, “How can I find a wife there?” and he threw up his hands. Well, we hadn’t yet visited Kodiak Island but we’d understood it was more famed for its huge brown Kodiak bears than for its eligible young ladies. “Pray for me, will you?” he said, turning to us. “Our Lord has called me, it was His Will I should do this. So I’m doing God’s Will. One has to show up. Here too, for this church: I’m showing up.”

My mind slipped back to the lady down in the shop; she’d seemed about the same age as him, selling Tlingit wares. Perhaps he was trying something there with her? But that was none of my business…

He took us over to the cemetery and we wandered round the graves. One was cluttered with garden ornaments, miniature wheelbarrows, a gnome leaning over a garden fork, another lying on its side nonchalantly, propped up on his little elbow with a dreamy look on his face. Further along a tiny polar bear stood stone upright at the head of an infant’s grave, surrounded by a scattering of toys the poor baby had not been granted time to play with. Sad infant graves which we walked round in silence, each grave with the three barred Orthodox cross.

We came back to the church steps again. Cyril sunk his hand into his cassock pocket and pulled out another pot of his King Salmon. “Take some,” he held the jar out to us. It was delicious and melted like salty cream in the mouth. Perhaps it was the unique setting, the blazing sun with the magnificent scenery and the tales told by this impressive friendly trainee priest which made it taste so wonderful.

We looked up at the eagle which was back circling round the dome. “I tell you, that’s my father watching out for me,” he said. “I am from the Eagle clan.”

“Tlingit, Eagle” my husband said, “a Tlingit Orthodox Eagle…” it was getting more fascinating by the minute.

We’d read about Christian missionaries in Alaska who suppressed traditional Native American ceremonies – particularly dancing – and who fiercely forbade the indigenous population from speaking their language, whipping children at school who dared slip up. But that was a long time ago.

“Ah, but the Russian missionaries were different,” he explained. “They let us speak our own language. And they let us dance. I have all my tribal wear and jewellery, I still wear them sometimes, I still dance. No, the Orthodox Church lets us have our ceremonies too. They are not incompatible. You saw in the church that we have the bible in local native languages, too.”

I remembered that the lady in the shop by the sand had someTlingit clothing for sale. Perhaps, I thought, she’d seen him all dressed up and what a sight it must be, this striking man in all his regalia.

Cyril went on to tell us he was raised in Sitka by his father. His father, now dead, had been an Orthodox priest. At first Cyril had resisted his father’s influence and enrolled in the Army where he stayed for six years. After that he was a truck driver in Philadelphia, and got married. Then something, we weren’t quite sure what, made him turn back to his father, respect what his father was doing and now here he was following in his father’s footsteps, training to become an Orthodox priest.

He looked up again at those outstretched feathered wings. “I tell you, he’s looking after me,” he repeated. “But I’ll need a wife. Please pray for me.”

Clamming in Ninilchik

Razor clams here are the size of babies’ hands

opened up to catch the midnight sun.

They roll in with the tide and lie on sand

full and fleshy, their tumbling journey done.

Above, a Russian church, its golden dome

a gleaming refuge for those who seek a home.

But eagles, ravens coast with eager eye

and clammers armed with spades and knives arrive –

clams bury downwards as the shadows loom

of wings or claws or the clammers spoon

a feast for those who have the craft to find

those rippled markings camouflaged like waves

in sand so fine which cossets them like babes –

babes of the sea who cry on land exposed

under cliff and cloud their little hands tight closed

while up above a Tlingit pastor’s hands

are held in prayer for those who come to land

in Ninilchik, in Cook Inlet, across a glacial bay.