At our New Year’s drinks party at the local Mairie (Town Hall) in rural Normandy, our regional MP dared speak up about French attitudes during this period of the longest strikes France has ever seen. She said we are getting a reputation as a nation of complainers, while there are nevertheless a lot of things that are good in this country. My counterparts, she said, in other European countries do not understand why we complain so much when we have a lot to be envied.

She said it with a warm smile but there were some raised eyebrows and the hall fell silent. Most of the people in our village are farmers and labourers. It is a well-known fact that farmers have been protesting against new farming regulations they have had to adapt to, often with little help in understanding how to go about it, and some still waiting for financial aid due. The latest complaints have been about their pensions, and the governement is at present focussing on how to redress the situation in their favour, recognising there must be room for improvement ; negociations are still underway and closely followed by the MSA, the Mutuale Sociale Agricole – the French farmers’ social security watchdog.

The French are a conservative people, not fond of change. But change, particularly in the farming sector, is an urgent necessity in this era of climate change. To address this emergency the government has created new, draconian regulations which have caused mayhem particularly for well-established farmers used to traditional methods : habits die hard in France.

So what does France have for others to envy?

Land. Cheap land.

This is one of the reasons why Dutch and Belgian farmers are here and still coming. In fact, if you are ready to battle your way through the administrative processes, France has a lot to offer in farming.

Dutch farmers coming to France

French farmers were not the only ones protesting last year. Dutch farmers were also protesting in the streets of The Hague, paralyzing the city. Why? It would seem for much more serious reasons: the Dutch government has proposed cutting farming output country-wide by 50% – particularly dairy farming – in the name of climate change, to limit greenhouse gases. Dairy farming is apparently producing too much nitrogen gas. Whereas Dutch farmers had the support of most of the public, Eurostat figures – albeit not quite up to date – do show the Netherlands at the top of the list for such emissions.

A Dutch farmer recently interviewed in the specialised press, came to France in 1991. Now going into retirement, he is helping both Dutch and Belgian farmers set up in France. Some buy land to farm, others rent it. Yes, he complains, the Dutch government is determined to reduce the number of farmers. Environmental regulations are tough enough for farmers in France, this farmer admits, but in the Netherlands, controls are severe and fines more automatically imposed than in France.

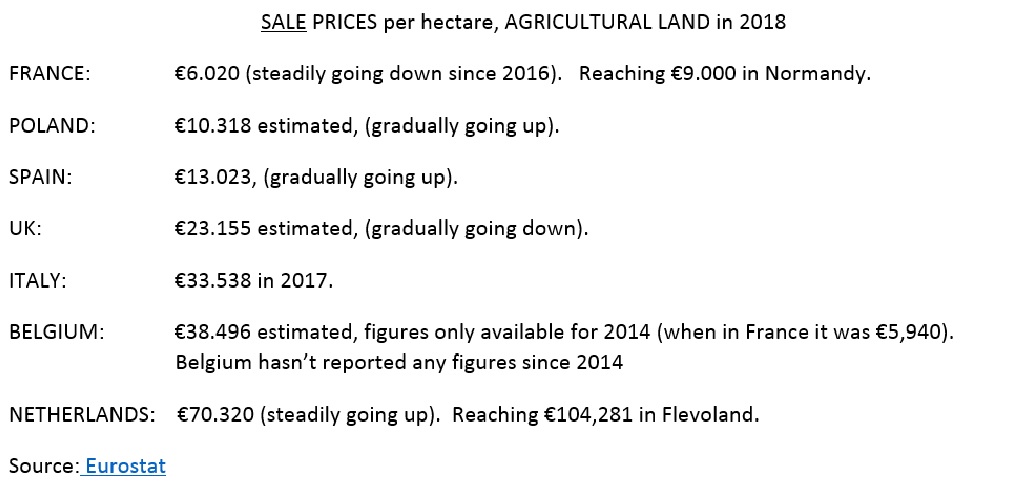

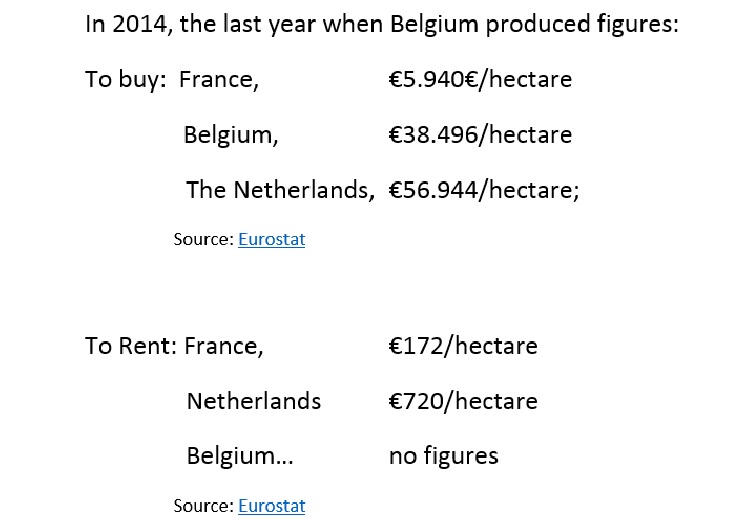

The main attraction is that farming land is still very cheap in France. One hectare of land costs around six thousand euros to buy here, whereas in the Netherlands it costs a staggering average of seventy thousand euros and can go up to more than €100.000/hectare in some areas (see figures below).

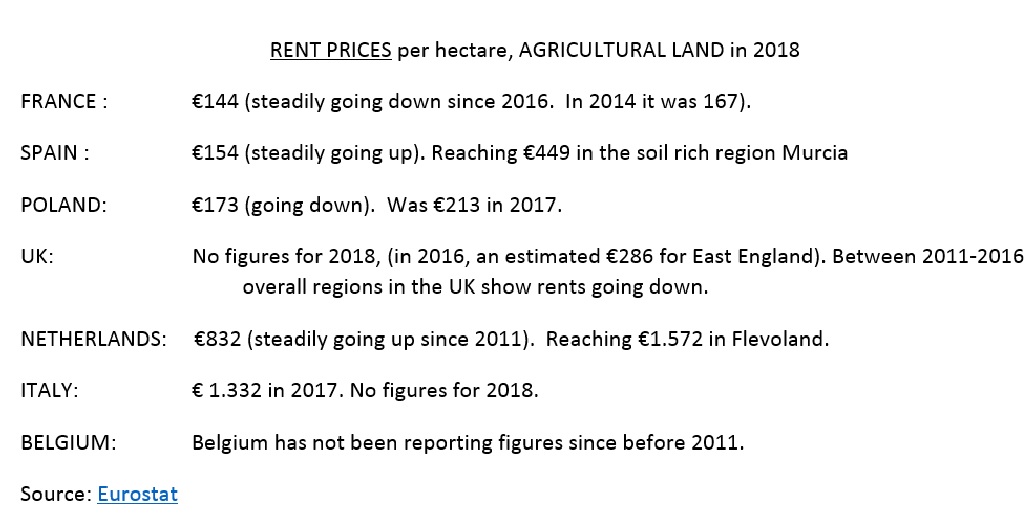

Renting French farmland is also very cheap, and available at a mere €140/ha (and the cost is steadily going down). In the Netherlands, where land is much scarcer, you can pay up to € 1.500/ha (one thousand five hundred euros per hectare) – or even more.

Another Dutch farmer who has recently arrived in France says that despite the language difference, and given the Dutch government’s pressure to stop cattle farming, he is buying land in France to set up a milk farm. And he intends to expand, something which would be unthinkable in his own country. But he is welcome here: note that in France, livestock went down by 183.000 between 2016 and 2019. He has the added problem that his present farm in the Netherlands falls within one of the Nature Protection Areas of Natura 2000*. Is he not worried about agri-bashing, on the rise in France, he is asked? Yes, he says, but it’s not only in France, the same thing is happening in the Netherlands.

I walked home with my neighbour after the New Year’s drink. “I’m glad she dared say that,” my neighbour said of our MP’s plea as we walked past the vast fields sewn with barley, wheat, later to be sewn with sorghum and flax, “it’s true, we do have so much land”.

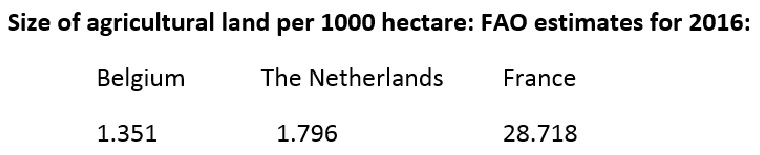

The FAO (Food and Agriculture Organisation) figures for 2016 show that France has 28.718 thousands of hectares of farming land, whereas Dutch farmland is 16 times smaller at 1.796. The Belgians have even less: 1.351.

French agricultural land is, however, on a steady decline; it is being nibbled away by ‘artificialisation’ or ‘concreting’, even if new laws exist to curb such activity, but between the apparent political will and reality… falls the shadow (to pinch T.S. Eliot’s quote).

My neighbour went on to complain about the spraying of these vast fields with goodness knows what pesticides. I found myself saying don’t complain… there are bio pesticides out there now which they must use: farmers have less and less choice to do otherwise.

Belgian farmers in France

Belgian farmers are coming to the north of France to rent land. Even if there is a history of Belgians farming over the frontier, mostly for potatoes and beetroot, a practice dating back to over a century, they are still coming. It is a complicated process to buy land in France so they rent, work the land and then take back their produce to Belgium, much to the irritation of locals. But there are enough French farmers ready to illegally sublet land to make a bit of extra money for themselves. It is a practice that isn’t monitored closely and suits both parties.

Figures for the cost of renting and buying in Belgium are not easy to come by, but historical figures exist and imply that it is much cheaper in France. The fact that Belgium has not reported such statistics to Eurostat since 2014 begs the question: how seriously does Belgium take its farmers when they resort to farming over the frontier?

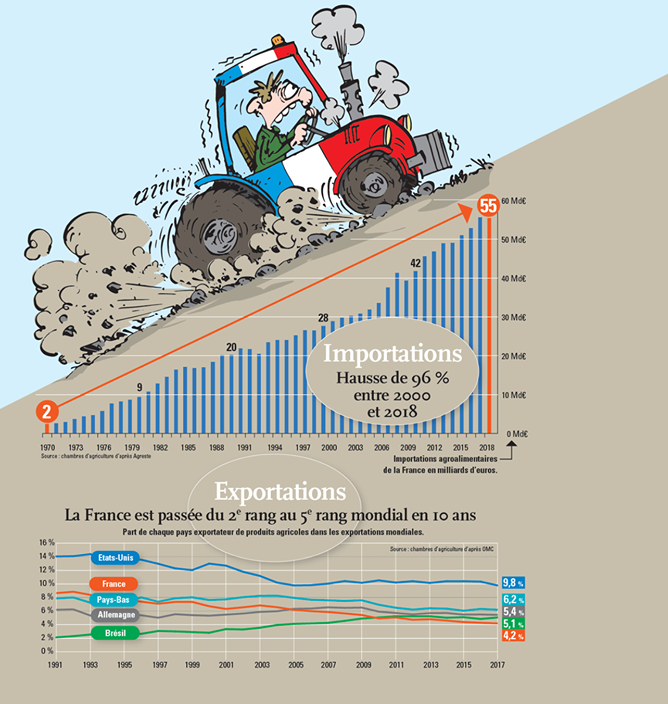

On the world market, French agricultural products are becoming less and less competitive.

What is hindering competition? The French Senate (last May) said that high labour costs are crippling French agriculture. The minimum wage and employer’s contributions are very high (43 % of gross salary, as opposed to 31 % in Italy and 21 % in Poland). The solution meanwhile could be to do what Belgium and Germany do: take on foreign workers because social charges due depend on their country of origin.

Always look on the bright side of life: Bio Market is still booming.

The low price of farming land is an incentive to anyone – French and EU nationals – wanting to go into farming. And in some areas such as here in Normandy, cattle farming is encouraged with a financial bonus for including at least one local breed in your herd.

Then there is the booming bio-market. Going back to my neighbour, she is not alone in growing a lot of fruit and vegetables in her large garden which she then shares amongst close neighbours. Our bard down the track has a large field where he also cultivates vegetables and fruit under soil conservation conditions, and has a ready clientele. Our bustling village grocery shop only sells local bio produce, although of course the wine and spirits served at the crowded counter come from further afield. Even in the nearest town, people are shunning the supermarkets and buying at the Associations who distribute local bio produce. Not only do we know what we’re eating, neither we nor the farmers need to pay overheads or any middlemen.

Whereas more and more locals watch with wary eyes those farmers who work vast swathes of land, suspicious that they may not be abiding by new regulations, they see bio farmers in a completely different light. Bio farmers, who also use bio pesticides, use much smaller patches of land for their crops and animals, and seem more ‘accessible’ because they have been clever to develop close contact with local people and thus give consumers more confidence. And it has paid off. Little by little consumers are learning what the process of farming entails. And they see exactly where it comes from: traceability of food is the buzz word, as is the new EU slogan for sustainable food: ‘de la fourche a la fourchette’ – ‘from farm to fork’.

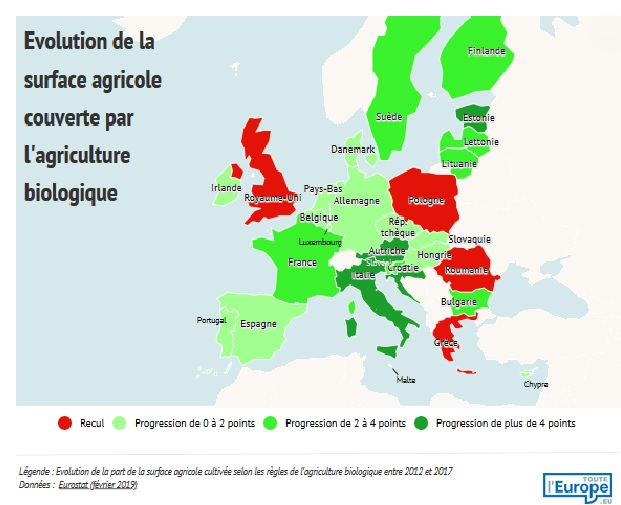

On a national scale, production and success in the bio sector is soaring despite administrative hiccups in the distribution of governmental subsidies. Bio production is up 212 000 tonnes from 2018, representing a rise of 157%, according to FranceAgriMer** (the national establishment for agricultural and marine products). Sales in AB products which can be used in bio farming have already doubled over 9 years a could be over 12 % in 2025, reports La France Agricole following a news conference given by the industrial union for the protection of plants/Union des industries de la protection des plantes (UIPP). And France is 3rd in the EU league table for bio products, behind only Spain then Italy, according to the Agence Bio. Bio production has shown it can help weave together local communities and improve the public perception of farmers.***

Social media to counteract agri-bashing

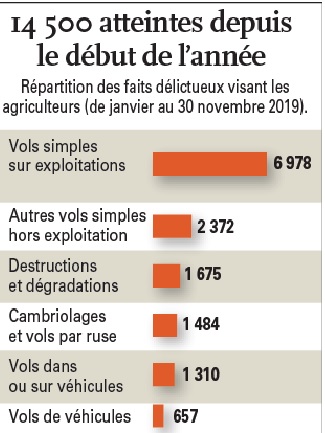

With agri-bashing on the rise last year – farms are being looted, burnt and defaced along with death threats from anonymous groups, farmers have been learning the importance of communication. They have set up their own social media tools to inform the public of how they work and what farming entails. Many people leaving the city for the country – the ‘neo-ruraux’ – complain about muck spreading, smells, and tractor noise …

To sensitise people to life on a farm they’ve taken to YouTube and other social media platforms to explain and show exactly what they do, what it means to be a farmer, and it goes for entertaining and informative watching. Take for example the “Youtubueur” in our Department, Agriskippy (Antoine Thibault, dairy farmer in the Eure). Others show videos of themselves working in the fields, show how they breed animals, how they test agricultural machines. All this with the idea of turning public opinion more in their favour. It is, after all, fundamentally they who feed us. The first 20 Agri channels (some since 2014) have grown 120% since they started up. And check out France Agri Twittos on Twitter: they have nearly 12 000 followers. And many farmers are also offering farm holidays for families to sensitise the public about their work.

But the public is still wary of pesticide use. Media hype on glyphosate has fuelled fears and journalists have not successfully reported on the more nuanced balance of glyphosate alongside other, more natural, methods which have been approved while awaiting alternatives.

The EU publishes restrictions and future bans on certain pesticides, but it is up to each country as to how to apply the rules. France – and this should be good news for consumers, if not very difficult for farmers – is more strict than most in bringing forward the EU proposed dates of bans. But the government has been over-zealous, and this was the main reason why President Macron’s first environment minister Nicholas Hulot resigned, taking sides with the farmers who needed immediate help with alternatives which were not forthcoming. Since then, the government has stepped back and, as the Dutch farmer mentioned above, fines are not as strict during this transition period as they are in Holland. And just last week, President Macron backed down on a complete ban on glyphosate by end 2020, pushing back the date until viable alternatives are available and accessible at affordable prices.

However, stricter regulations on ZNTs – non-spraying zones known as ‘Zones Non Traitables’ – those areas in fields which are right next to schools and homes, are now being applied. The idea is to protect the local population, but it has meant a substantial cumulative loss of land for farmers who are asking for compensation which is still not forthcoming.

Indeed France has been tougher than other EU countries when it comes to exemptions : take for example neonicotinoids: whereas exemptions from the ban were allowed in Belgium, Poland, Austria and Finland, in France they were not. And French farmers are paying an increase of €1.500 per year on taxes on pesticides. (See more on neonicotoids here and here.)

To finish on a positive note, and to summarize:

- In the aftermath of the French pension reform demonstrations, farmers have won their fight to have their pensions increased.

- Organic grain crops were up 212 000 tonnes in 2019; over 5 years they have risen 157%.

- 6 million hectares of land went to bio farming last year, up 17 % since 2017.

- Between October 2018 and 2019 Bio milk went up 16%.

- Bio farming comprises 9.5% of all agriculture in France.

- In 2018, land converted for the first time into bio farming was up 31 %, representing 268.000 hectares.

- The government is actively encouraging methanisation projects – projects increased tenfold last year 2019.

- Anses (French Agency for Food, Environmental and Occupational Health & Safety), although criticised for its slowness, constantly checks on food safety and products.

- Farmers are no longer the faceless people who cultivate vast swathes of land but are being seen, thanks to the Jeunes agriculteurs (the Young Farmers Union, for farmers under the age of 35) who are excellent communicators, and agriculture bloggers who explain to the public what they are doing and thus make the consumer feel more confident.

- In comparison with most other European countries, France is way ahead in bio conversions: surpassed only by Spain and Italy, according to Eurostat.

-

The French Young Farmers Union (Jeunes Agriculteurs) is made up of French farmers under the age of 35 and is apolitical and independent. It has 14 regional structures and 95 departmental structures representing all sectors of farming production in France.

——————————————————————–

*See this website for the share of Natura 2000 sites in the EU.

**figures given by FranceAgriMer and quoted in La France Agricole.

*** See Bio facts and figures for France in 2018 , published by French ‘Agence Bio’ here.